1.3 Leadership

Leadership in research involves influencing people in order to achieve a research goal. It also involves having a vision for the project and its future, and promoting the right culture among the research team.

While it’s easy to recognise leadership, there are no universally accepted theories to explain it. Effective leadership behaviours are suggested below. You might want to engage with any or all of these behaviours and create your own personal leadership style.

One model of leadership strongly supported by the literature is ‘transformational leadership’. Research leaders who engage with this style may lift team members to higher levels of performance through the methods set out in the following table.

Intellectual stimulation |

Encouraging others to see what they are doing from new perspectives |

Inspire others to consider the benefits of the completed research to the university and community |

Idealised influence |

Articulating the mission or vision of the research project |

Regularly communicate the potential goals of the research to keep team members interested and on track |

Individualised consideration |

Developing others to higher levels of ability |

Carefully understand the current skills of the research team members and seek to stretch and develop them |

Inspirational motivation |

Motivate others to put organisational interests before self-interest |

Leaders and managers need to set a good example of dedication and commitment; stretching others by expectations; providing support with regular staff social events (some of which may involve team members’ partners and spouses) |

An effective leader of a research team will:

- Show genuine concern for team members

- Be accessible to team members

- Enable and encourage them

- Display honesty, dedication, integrity, and consistency

- Be decisive

- Assist to resolve complex problems that staff have

- Encourage networking

- Keep the focus

- Keep communicating the vision

- Support a positive culture.

Arvonen (2002) has identified the different behaviours of leaders and managers, and these can be translated into research terms. Both sets of behaviours are necessary for a team to meet its goals.

Leadership

- Offers ideas about new and different ways of doing the research

- Makes quick decisions when necessary

- Consistently pushes for ways to improve the research and research culture

- Likes to discuss ways of improving the current research project and ideas for future, related research projects

- Is willing to take risks in making decisions

- Is open-minded

- Is future focused.

Management

- Plans the current research project carefully

- Defines and explains the work requirements clearly to members of the team

- Is very exacting about plans being followed

- Gives clear instructions

- Creates order

- Analyses and thinks about the project carefully before making decisions

- Makes a point about following rules and principles.

Note that these two sets of behaviours are significantly different.

The research leader's behaviour tends to be divergent while the research manager's behaviour tends to be convergent. The manager assists in reducing variation in outcomes, which is a quality function. The leader maintains focus on the vision despite the problems which inevitably occur.

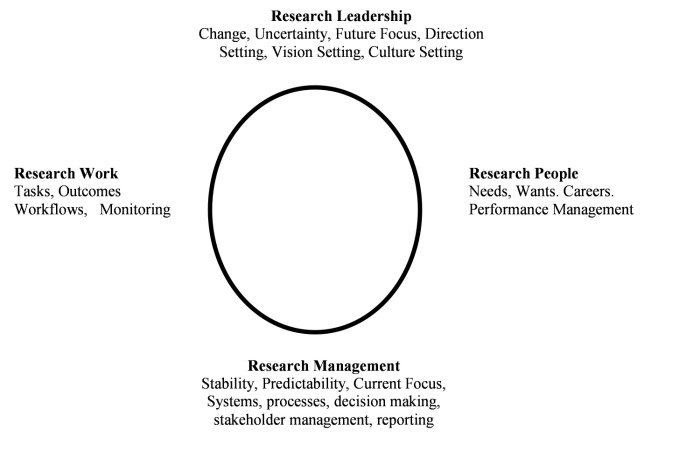

The following diagram represents the connections between research leadership and research management, and the relations between the research team and outcomes. All four of these domains need to be monitored and supported by the research leader.

As the team matures, the leadership behaviour that assists the team’s development changes. Initially, it will focus on the task to be achieved and the role of the people involved. Subsequently, building relationships between team members becomes just as important, until eventually there is a shared understanding and support for the group and its goals.

Crawley (1979) reinterpreted an earlier theory of Tuckman (1965) and his work can be applied to the research team in the following way.

Forming |

Identifying a research group’s vision and obtaining agreement about it |

Clarification of the research task. Promoting interaction. Providing guidance to let members feel safe to show initiative |

Storming |

Development of a more detailed understanding of the research task and how it can be achieved |

Provide a sense of security, holding the research group through difficult periods. Showing that the leader is strong and competent but not inflexible |

Norming |

Developing procedures for achieving tasks |

Development of detailed procedures. Identification of tasks. Allocation of roles to complete tasks. Modelling of appropriate behaviour. Validation of helpful behaviour. Clarification of boundaries and rules. |

Performing |

Identifying activities to achieve the task. Concern for quality |

Monitoring progress: reinforcing the importance of quality, consistency, and allowing for a work–life balance |

Adjourning/Terminating |

Completion of the research tasks: did we achieve what we set out to do? |

Assisting in the successful completion of the task and encouraging thoughtful reflection of the process |

Supporting these stages of development in research teams requires an understanding of the degree of competence or capability of each individual. By having this understanding, the right form of leadership can be applied.

Tuckman (1965) described the stages of team development as:

Forming

Members of the team are identified and begin to get to know each other. Members look to the leader for direction in their tasks and for recognition and benefits. Team leaders need to be fairly directive during this phase. The team leader provides attention and resources to those team members who actively comply with his or her expectations and engage with the tasks required, and ignores those who don't. This results in people having different status within the group.

Storming

Team members may express their ideas of how the project should proceed. A subgroup or individuals may challenge the leader and the atmosphere can be unpleasant and contentious. Group members, or the disaffected, provide support for each other so the leader is no longer the sole source of support and reward for some members. More energy and attention is spent in dealing with the interpersonal issues than on the task. Team leaders during this phase may be more accessible but still need to be fairly directive in their guidance, decision making, and professional behaviour. This phase may last a short or long time depending on the maturity of the members and the patience and negotiating skills of the leader.

Norming

The team identifies their commonality, forming a cohesive group that is defined by adherence to a set of group norms. Team members, including the leader, support each other. However, the team does not accept the views of people who think differently to the group norms. Teams in this phase may lose their creativity if the norming behaviours become too strong and begin to stifle healthy dissent. The phenomenon of 'groupthink' can be one outcome of this stage of team development. Leaders tend to be more participative than in the earlier stages. Team members can be expected to take more responsibility for making decisions and for their professional behaviour. By reiterating the common goal and by supporting the expression of different views (even if they challenge the group's thinking and even if the conclusion is not accepted), the danger of this phase can be addressed.

Performing

At this stage the team will support autonomous action by members, challenging their ideas but respecting their differences. The binding factor is the purpose or goal for which the team was established. The leader's role is participative within the team, although he or she may need to refocus work on the vision and key output of the project and represent these to people outside the team.

Adjourning/Terminating

When the team's goal is reached (or the funding finishes), the team is disbanded. Typically, people feel a sense of loss as the bonds dissolve and a ritual to mark the end helps to celebrate the achievement and recognise that the task is complete. Finalising records can be seen as a way of leaving a mark or legacy.

By understanding the phases in team development you can introduce processes to assist the team move through the formative stages to an autonomous, high-performing team. Building opportunities for all team members to express their points of view and for the group to decide how it will deal with interaction problems, you can build bridges that make the team perform highly.

Awards that acknowledge staff whose contributions have helped the team be more effective encourage members to add to the common effort rather than just meeting their own goals. Although the award doesn't have to be expensive, it must be meaningful to the individual and the group.

Within teams people tend to adopt different roles. Research has shown that effective teams have members who undertake a range of roles. This includes those who:

- generate and assess new ideas

- apply new ideas

- win support by attracting resources

- provide direction

- support members

- complete outcomes

- monitor the social and ethical impacts.

Hersey–Blanchard Theory

An alternative research style comes from Hersey and Blanchard (1999). They suggest that the leader's behaviours must correspond to the developmental level of the follower – and it’s the leader who adapts.

For example, a new person joins your team and you're asked to help them through the first few days. You sit them in front of a PC, show them a simple set of results that need to be analysed today, and leave to go to a meeting. They're at level S1, and you've adopted D4. Everyone loses because the new person feels helpless and demotivated, and you don't get the data processed.

On the other hand, you're handing over to an experienced colleague before you leave for a holiday. You've listed all the tasks that need to be done, and a set of instructions on how to carry out each one. They're at level S4, and you've adopted D1. The work will probably get done, but not the way you expected, and your colleague despises you for treating him like an idiot.

But swap the situations and things get better. Leave detailed instructions and a checklist for the new person, and they'll thank you for it. Give your colleague a quick chat and a few notes before you go on holiday, and everything will be fine.

By adopting the right style to suit the follower's development level, work gets done, relationships are built up, and, most importantly, the follower's development level will rise to S4, to everyone's benefit.

Four different styles of leadership are:

- Directing (D1): Leaders define the roles and tasks of the 'follower', and supervise them closely. Decisions are made by the leader and announced, so communication is largely one-way.

- Coaching (D2): Leaders still define roles and tasks, but seeks ideas and suggestions from the follower. Decisions remain the leader's prerogative, but communication is much more two-way.

- Supporting (D3): Leaders pass day-to-day decisions, such as task allocation and processes, to the follower. The leader facilitates and takes part in decisions, but control of the specific tasks is with the follower.

- Delegating (D4): Leaders are still involved in decisions and problem-solving, but control is with the follower. The follower decides when and how the leader will be involved.

The appropriate leadership style for the different levels of team competence and commitment are listed below:

Directing D1 |

S1: Low Competence–

Low Commitment |

Generally lacking the specific skills required for the job in hand, and lacks any confidence and/or motivation to tackle it |

Coaching D2 |

S2: Some Competence–

Low Commitment |

May have some relevant skills, but won’t be able to do the job without help. The task or the situation may be new to them |

Supporting D3 |

S3: High Competence–

Variable Commitment |

Experienced and capable, but may lack the confidence to go it alone, or the motivation to do it well/quickly |

Delegating D4 |

S4: High Competence–

High Commitment |

Experienced at the job, and comfortable with their own ability to do it well. May even be more skilled than the leader |

As we’ve previously seen, research management requires different skills and allocates different responsibilities to research leadership. Research management involves identifying work requirements, recognising the size, complexity, and scope of the research project, and implementing an appropriate structure.

There are a number of project management tools and methodologies that can be used and adapted in order to identify the activities for your project, for example, the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide). Supervision of staff is a major task, but if the team is small this will not be too difficult and it will rely mainly on your dealing with a few people. If the research team is large you will need more formal structures, including job descriptions and regular performance reviews. You will need to gauge whether staff appointed to the team require training to complete their appointed roles.

On a medium or large research project you will need to think about how you can attract and retain administrative staff. Organisations are confronting an increasing difficulty in attracting and retaining good staff – and readvertising, reinterviewing, appointing and training staff is a distraction for research leaders. You need to make it clear to support staff what you expect in order for them to complete their job. This will reduce your need to micro-manage the administrative process, and there will be less confusion over the functionality of each role. (Supervision is discussed further in Topics 3 and 4)

In summary, a number of leadership models have been discussed. To apply them effectively, as a research leader you will need to decide which model is most relevant to your project and to the stage of your team’s development.

References

Arvonen, J. (2002). Change, production and employees (PhD Dissertation, Stockholm University, 2002). Scandinavian Journal of Management, 18(1), pp. 101–112.

Bass, B. M. (1985). Leadership and Performance Beyond Expectations. New York: Free Press.

Bass, B. M. & Avolio, B. J. (eds) (1994). Improving organizational effectiveness through transformational leadership. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Bass, B. M. (1997). Does the transactional transformational leadership paradigm transcend organizational and national boundaries? American Psychologist, 52, pp. 130–139.

Crawley, J., (1979). The nature of leadership in small groups. Small Groups Newsletter (Australia), 2(3), 28–31.

Hersey, P. & Blanchard, K. H. (1999). Leadership and the One Minute Manager. New York: William Morrow.

Remington, K. (2011) Leading Complex Projects, England: Ashgate Publishing Company.