2.1 The nature of a research team

Research projects

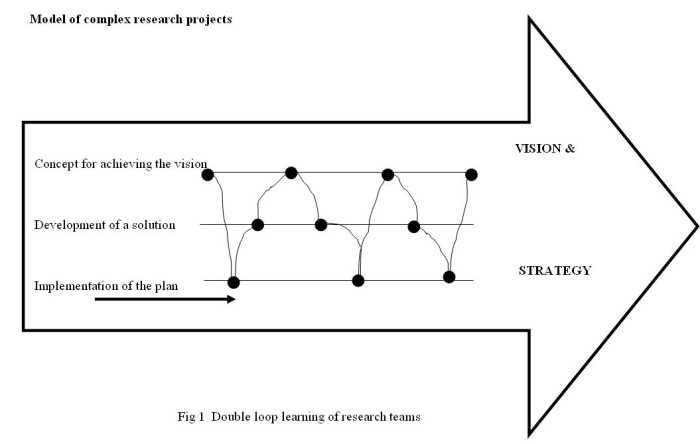

Research projects are undeniably complex. The research goals, or at least the method of achieving the goals, are likely to be unclear when the project is first planned (see Module 1: Research Strategy and Planning, Topic 4.1, "Types of research projects"). To achieve the desired results, the research team in such a project typically needs to learn new strategies, tactics, and skills along the way. This is known as ‘double loop’ learning. The research team will probably need to cycle back and forth between the concept for the research, the development of a solution, and the implementation of the solution.

Team composition

There are significant advantages to research teams being multidimensional, that is, with members coming from different backgrounds and disciplines, and having different degrees of experience. This kind of diversity brings the advantage that team members can learn from each other and may come up with new ideas by combining their skills. Creativity and motivation are greater in teams whose members have different skills. However, for cohesion, a certain level of overlapping skills is desirable.

Cohesion of a team of different specialists needs to be actively managed, since their differences may lead to conflict. It is an advantage if members of the research team are fairly emotionally stable. Self-confidence is required because team members will have different perceptions and different views of the research problem, and there can be greater insights if these differences are constructively explored rather than ignored.

Group cohesion is lower if team members differ greatly in how comfortable they are with levels of uncertainty. Some members of the research team may demonstrate anxiety and feel insecure when confronted with ambiguous research problems and tasks. This will have a negative effect on team performance. Others may respond completely differently and not see a threat but a challenge. You can prepare your team in advance for the potential challenges that are a normal feature of research projects.

Research leaders need to be careful when subgroups with similar attributes form since this can produce tensions within the larger group. A classic example is when all the senior team members are of one gender and all the junior members are of the other. Similar divisions could be based on disciplinary lines. This can produce a 'them versus us' mentality. It is better to have a diversity of characteristics to dilute potential factions and conflict.

Leaders of research teams are faced with a complex situation in that they have to achieve the research objectives, including completing on time and within budget, while helping team members develop their own competencies. Many research studies show that for a research team to function successfully, leadership is highly important. The leader has to adopt a leadership style that fits in with the general research environment, the objectives outlined in the grant application, the discipline being studied, the characteristics of the team itself, and the needs of individual team members.

Studies on research leader behaviour show that, to achieve good research results, a combination is needed of consultative leadership style, empowerment of team members, clear research goals, and a degree of research leader charisma. Stoker (2001) found the relationships shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Research leader and team characteristics

Team processes and issues

A team is greater than the sum of its parts. Research suggests that, in addition to the leadership styles, member behaviours, and attitudes shown in Figure 1, effective research teams also need to identify who belongs to the team, how decisions are made, and what management supports are available. Coordinated effectively, these characteristics will produce desirable research outcomes.

O'Connor et al. (2003; p. 361) provide some good advice to consider as you establish and work with your team.

1. Build teams based on the skills and characteristics required as well as interests/motivation and willingness to cooperate.

2. Expect team fluidity as members come to understand the workload, difficulties associated with learning others' thought styles, and the need for flexibility in the interpretation of the research question and how it impacts on them.

3. To help ensure continued motivation throughout the term of the project, clarify the importance of the research question and the multiple objectives associated with answering it. Express personal career objectives as part of this (e.g., tenure or promotion).

4. Be as explicit as possible about rules, policies, and work process issues, but also clarify the issue of ‘learning how to learn’ as a group. Make this the responsibility of the group, and implement ways by which team members can make suggestions about work processes.

5. Reduce perceived risk by clarifying publication outlets, and gaining signs of legitimacy both within and outside the university. External funding and key partnerships help.

6. Set norms/expectations regarding the research process. Allow for continued learning and change. Identify multiple participation levels and clarify expectations regarding outputs at each level. Communicate to all team members the participation level expected from each, so members know what they can appropriately expect from one another.

7. Build in a set of security mechanisms regarding paced dissemination, rules for co-authorship, and an understanding of who owns the data so team members are clear about what level of risk/reward is associated with participation in the project.

8. Build in mechanisms for periodic team composition assessment and renewal.

9. To ensure continuity, identify core team members who will collect data across all cases.

10. Mix subteams of interviewers so that they hear, over the course of a site visit, every other team member's questions on each case.

11. Develop decision rules about how to manage the interview meeting so that each researcher gets appropriate time needed and so the team of researchers together probes insights beyond what a single interviewer could do.

12. Maintain a central storehouse of data for all to access.

13. Provide frequent, periodic delivery events that require researchers to confront the data and prepare for interaction with an external audience.

In choosing team members you should note that more effective research teams are composed of members who are:

- More highly rated as individual performers

- More satisfied as to their professional needs

- Perceived by their teams as more willing to take calculated risks

- More willing to trust other team members

- More willing to encourage cohesiveness.

The major challenge of leading research lies in dealing with the uncertainty of not knowing whether you can produce results having significant impact. This has implications for the nature of the team environment you develop and manage, your leadership style, and the characteristics you look for in the group you lead.

References

Jain, R. K. and Triandis, H. C. (1997). Management of Research and Development Organisations, New York: John Wiley.

O'Connor, G. C., Rice, M., Peters, L. and Veryzer, R. W. (2003). Managing interdisciplinary, longitudinal research teams, Organisation Science, 14(4), July–Aug, 353–373.

Stoker, J. I., Loosie, J. C., Fisscher, O. A. M. and de Jong (2001). Leadership and innovation: relations between leadership, individual characteristics and the functioning of R&D teams, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 12(7), 1141–1151.