April 16, 2021

URCS Secretariat

Australian Government Department of Education, Skills and Employment

Introduction

Thank you for the opportunity to respond to the University Research Commercialisation Consultation Paper released on 26 February 2021.

Please note that this submission represents the broad, collective views of the Go8, Australia’s leading-research intensive universities with seven of its members ranked consistently among the world’s top 100 leading universities. Each member Go8 university may submit its own related submission.

Also note that the Go8 approves this submission for public release and does not wish any of it to be treated as confidential.

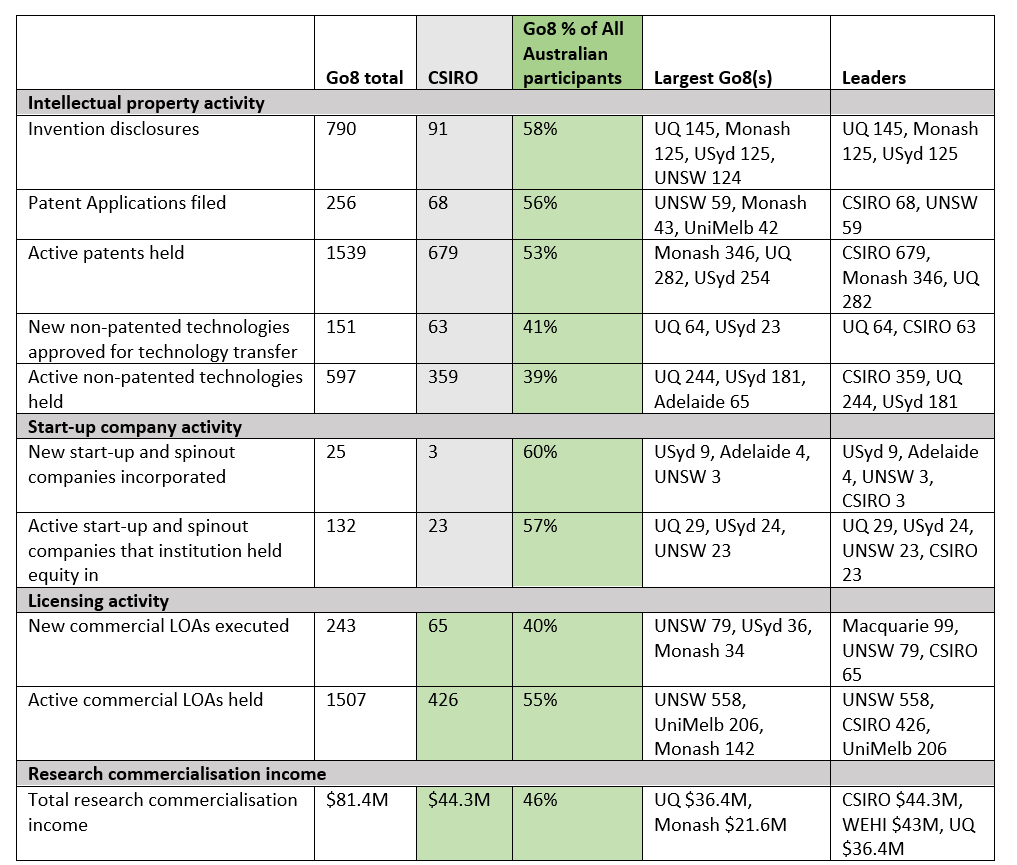

By way of context, the Go8 undertakes 70 percent of university-based research in Australia and secures research funding from industry and other non-government sources which is twice that of the rest of the sector combined. In 2019 the Go8 collectively earned $81.4 million in research commercialisation income, and we were responsible for the majority of Australia’s new and active start-ups and spinouts attributable to public research and the majority of active licences, options and assignments (LOAs), outperforming the CSIRO in each of these categories.[1] The Appendix to this submission contains further details.

Given this role as the heavy lifter in the research and innovation space, the Go8 recommends that research commercialisation be treated as an integral part of an innovation and translation system, which:

- Is underpinned by an expanded national core of research and data infrastructure;

- Includes both research and higher education (the two mainstays of universities);

- Is built around an innovation ecosystem which includes more basic and applied research and connects these better through sharing of discoveries, and establishes an incentive gradient in favour of translation and impact;

- Has multiple translation pathways (among which commercialisation is but one); and

- Includes a funding system that reflects the innovation pipeline and includes industry, venture capital, government, and philanthropy.

Against that framework, the Go8 welcomes the explicit acknowledgement of the critical role commercialisation has in driving Australia’s future economic prosperity. Our universities can increasingly point to major commercialisation deals from our research. Over decades, our universities’ discoveries, founded on basic research, have proven to be a substantial advantage when it comes to evolving ground-breaking solutions or inventions, not least in the last year when Go8 members actively and significantly contributed knowledge and expertise in Australia’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Nevertheless, much remains to be done to ensure that the excellent research undertaken in Australia is optimised to contribute to new solutions, products, remedies and technologies and can spark and sustain new industries and markets. We need to establish a framework for success if Australia is to achieve genuine scale-up of commercialisation based on our university research.

The Go8 universities’ collective and individual track record in research translation and commercialisation reflects the persistent effort and commitment of dedicated divisions and staff to capitalise on opportunities despite the currentrisk-averse, disjointed and insufficiently resourced system.

A sustained, thorough and informed national campaign is needed, characterised by positively incentivised academics and business (including SMEs), recognition of translation skills and experience; including a steady flow of research sufficiently validated through proof-of-concept processes to raise investor and industry appetite, and readily attainable capital to advance commercialisation.

There is a risk however that an expectation of short-term wins, that disregards the building blocks of later discovery that fundamental research enables, and the longer timeframe needed to embed change – let alone reflect commercialisation cycles – will hinder progress.

There are many factors and aspects to research commercialisation, not least of which are an appetite for risk and a willingness to fail. It is not simply a matter of taking university knowledge and converting it.

Recommendations

As Australia’s leading

research-intensive universities, which spend $6.5 billion on research annually, the Go8 presents a series of key

recommendations that are necessary to sustain and boost the commercialisation

output of university research. The enabling recommendations outlined below will

also underpin the success of the key recommendations and the ongoing evolution

of Australia’s commercialisation and translation ecosystem.

Key recommendations

- Support for basic research.

As a first principle, the Go8 advocates for the Government’s continued recognition of and support for basic research as an essential part of the knowledge spectrum on which not only commercialised or translated products and outputs are reliant, but upon which discovery and understanding of current and future problems is predicated. Key advice to Government on research has consistently supported this view, most recently by the newly reformed Industry Innovation and Science Australia (IISA)[2]. It is also worth noting that the first proposed budget plan of the Biden Administration includes increased funding for basic research via the National Science Foundation (NSF), even whilst putting a clear emphasis on applied research and development programs.[3]

- Enhanced proof of concept funding.

The key bottleneck in the commercialisation of university research is funding at the proof-of-concept stage that converts breakthrough research into opportunities that are suitable for business or Venture Capital (VC) investment. Currently there are only limited funds available for this stage of commercialisation and this is often funded by universities themselves by cross-subsidising from other activities. This is where there are the highest risks and the greatest chances of falling into the so-called ‘Valley of Death’, driving Government concerns that there are insufficient ideas to commercialise.

- Positive incentives for university researchers to commercialise and work directly with industry.

Universities need to continue to drive genuine cultural change in its research workforce. Researchers must be incentivised to collaborate with industry in a way that ensures career progression and promotion based on such collaboration. These incentives should also ensure genuine researcher mobility between universities and business.

- An approach informed by Australia’s SME-dominated business environment.

Australia’s business environment is dominated by SMEs and with this comes constraints on both the ability to absorb research and to actively engage in research with university partners. These constraints, including resourcing – in terms of cash flows and research literate staff – could be addressed through changes to the R&D Tax Incentive (RDTI) and workforce mobility. Business access to university research infrastructure should also be recognised and encouraged.

- Raising business awareness and ability to take up university knowledge.

Support is also needed to enable businesses to both understand the opportunities that academic knowledge presents and to access those ideas, whether this be through work exchanges/mobility or joint placements; providing tours of university laboratories and genuine promotion of innovation precincts as an avenue to collaboration and commercialisation. Successful Government programs that foster intermediaries and systemically raise connections between business and universities – such as Innovation Connections and CRC-P programs – should be expanded.

- Government coordination and priority setting

Part of the role of Government in the commercialisation space is to establish national priorities that identify national competitive advantages and sovereign capability needs. Government should then target funding to these priorities and ensure that there is a whole of Government approach (across multiple portfolios) in coordinating and supporting these priorities. Programs that provide this support should have the longevity and continuity that enables business to learn to work effectively with them.

- An Australian Translational Research Fund

With key recommendations 1-6 in train, Australia will need to take full advantage of its improved commercialisation landscape, architecture and wealth of basic research with a fund for non-health disciplines which supports research commercialisation in priority areas. The design of such a fund should concentrate on enhancing the absorptive capacity of industry and universities to identify, nurture and scale new ideas and enterprises. This will enable stronger understanding of supply chains, business needs and skills, providing the basis for deeper, longer term collaboration. It would ideally be governed by the ongoing advisory committee proposed below (see: Enabling recommendation 2). While the fund is discussed as a concept in the body of this submission, the Go8 would be pleased to provide greater detail on a proposed scheme.

Enabling recommendations

- That the Government commit to a principle of ongoing co-design involving industry, universities and government of any material initiative to uplift Australia’s research commercialisation performance.

- That the Australian Government establish an ongoing advisory committee, potentially building on the existing advisory panel, comprising university, industry, SME and government representatives, to advise it on specific research commercialisation opportunities and gaps in Australia, and to champion key initiatives including in defined areas of priority.

- The committee should have a function to nuance the understanding of the problem of low research commercialisation in Australia, consider and fine-tune specific solutions to resolve this problem, and clarify the exact cause and effect relationship between industry-university collaboration and research commercialisation.

- The committee’s advice would be informed by key findings presented to Government, including those not public, relating to the lessons, outcomes and impact of the Government’s historical efforts to address the research commercialisation issue and the industry-university nexus, alongside the multiple previous reviews on these matters.

- That the Australian Government takes a persistent and coordinated approach to embedding research commercialisation as a major priority across its portfolios, and consistently champions university knowledge to industry and other stakeholders via its funding programs, strategies and new initiatives.

- That the Government work with universities and industry to establish clear overall and sectoral targets for research commercialisation, with stepped out measures and necessary incentives for achieving these in the next five years and seek to regularly refresh this ‘roadmap’ as an instrument for continued effort across electoral cycles. Effective metrics are also needed to gauge and refine progress.

- That the Government commission work to forecast the extent to which Australia can lift university research commercialisation and over what time period, given a range of circumstances and conditions. Given the predominance of SMEs in Australia’s business sector, this work should include a detailed investigation of the role of SMEs and how to raise their uptake and capacity to absorb university knowledge and innovation.

- That a mapping of existing and historical measures in Australia to promote and drive university research commercialisation within institutions forms the basis for understanding progress in the last 20 years, where and how success occurs, what factors lead to a lack of pursuit of commercialisation or its failure, and whether there are any home-grown models peculiarly useful to our country’s context. Success and failure should be viewed as a spectrum, given that any progress along the pipeline both informs future effort and generates new skills and capability.

- That distinct funding streams and greater focus be placed on the importance of early stage or proof of concept funding to ensure that more ideas are validated sufficiently for them to be advanced into the commercialisation cycle.

- That the skills and workforce needs arising from the acceleration of university research commercialisation be clearly understood and matched with commensurate effort by government, universities and industry working together to build the capability needed, including but not limited to incentives and rewards. It is also important to recognise where Australia has skills gaps that cannot be filled without the recruitment of key international talent, particularly in terms of high-quality PhD students, who can help build national capacity in new and emerging industries.

Further Discussion

The Go8 considers many tenets in the Department’s consultation paper to be only partly true or misleading. To contend that a focus on university research would be a new approach, that settings favour pure research and universities have weak incentives to commercialise, dismisses the recent reforms of the Research Block Grants and the ARC Linkage Projects as well as reforms to measure the impact of research introduced by the National Innovation and Science Agenda (NISA). It also disregards initiatives such as the Go8 securing a $200 million partnership with IP Group to assist further commercialisation of research.

A more careful and precise definition is

needed of the

problem and what specifically in the Australian context reinforces the status

quo, preventing progress, as a precursor to determining the most

workable and sustainable solutions.

There are fundamental questions that could be explored further by Government, universities and partners to advance and fine-tune the thinking and proposals, in order to effectively set the environment up for success. For example:

- What levels of commercialisation can realistically be reached given the dominance of SMEs – with a far lower historical level of innovation than large businesses[4],[5] – in the Australian market, without significantly boosting their absorptive capacity, removing barriers and incentivising greater collaboration?

- How precisely industry-university collaboration fosters research commercialisation, and how understanding this can assist in sharpening the measures to drive commercialisation?

- Why failure may not be absolute failure. That an innovation did not proceed to commercialisation does not diminish the positive collateral or network effects elsewhere of the infrastructure established to support it or the skills developed in advancing it. Nor should success only be measured by those projects that are ultimately commercialised – metrics should also include how many are advanced some way down the pipeline.

- The outcomes of the Government’s historical efforts to address this issue, and what we can learn from those, such as the aforementioned NISA measures, as well as revisiting previous evidence-based reviews and recommendations.

- Whether insufficient time has passed to understand (and perhaps accumulate) the impact of recent reform, noting especially the long timelines of research translation and commercialisation[6]?

It’s about the people and our own context.

Research commercialisation is primarily about people – not projects. Policy needs to incentivise support for entrepreneurs. We support the establishment of an Australian specific model based on our experiences and success, to complement appropriate examination of international exemplars.

It is not impossible for universities to effectively translate research in isolation. There are singular examples that can be celebrated and drawn from to better gauge what conditions contribute to success and what hurdles and challenges needed to be overcome. However, the capability to translate our research in such ways must be sustainable and sustained; for example, the University of Queensland’s commercialisation arm, UniQuest, has been extraordinarily successful[7]. It would be remiss to dismiss success of this kind, rather than forensically learning from it. UniQuest’s major experience gathered over 30 years in driving its commercial outcomes and expertise in deal-making could help inform an Australian approach to fostering research commercialisation.

The Go8 universities have historically had a comparatively strong record in commercialisation among their university peers. The Go8 record for 2017-2019[8] compares favourably to CSIRO with strong Go8 performance in many areas including commercialisation revenue and new start-ups and spinouts.

Go8 universities also have a growing record of major partnerships with multinationals and major Australian companies in deriving tangible R&D-based solutions to real-life problems, major research translation examples and demonstrated how well they can work with others in addressing the COVID pandemic[9].

Similarly, there are insights to be gleaned from collective effort such as the joint commercialisation fund between CSIRO and four Go8 universities, Uniseed, Go8’s partnership with IP Group in a $200 million commercialisation deal signed in 2017 which has so far closed 12 funded Go8 innovations, and Cicada Innovations involving three Go8 and one non-Go8 universities for technology incubation. Major innovation precincts involving Go8 universities have also emerged[10]. These should be considered as ongoing duplicable mechanisms in commercialising research. This effort should not be compromised by inappropriate implementation of the Government’s precincts statement[11].

As a specific way of building the necessary culture for research commercialisation, the Government has a particular role and platform to promote further understanding across industry and universities. This is via its programs and policies. For research commercialisation to succeed, it will need to be consistently promoted and upheld by Government. Conversely, Government will need to be clear about what its expectations are and in what contexts it expects research commercialisation to take precedence: for example, if there are areas it does not expect university research commercialisation to inhabit, and rather intends industry to innovate mostly through collaboration with other businesses or overseas stakeholders.

Lessons can and must be drawn from specific sectors; for example, the defence or space sectors could be examined for relevance across other sectors, championed by Government portfolios.

Diverse Government policy and initiatives can better interact to ensure that any measures to enhance research commercialisation are best placed to succeed. Greater strategic alignment between the Education and Industry portfolios as the two policy leads concerned may be needed. At an operational level this would also be useful.

As the Go8 has previously advocated[12], the RDTI cannot be disregarded as a mechanism to drive industry engagement with universities, given it is the single largest measure to support business R&D.

It’s about a comprehensive expansion of our commercial potential

To draw together and capitalise in the long-term on the thinking and building blocks discussed, the Go8 recommends the Government establishes an Australian Translational Research Fund, at the heart of which is a nexus of people, ideas, and funding.

In this context, translation is the flow of ideas, whether emanating from basic or applied, curiosity-driven inquiry or solving industry problems, and whether into inventions, transfer of knowledge, policy, or commercialisation as start-ups and licences.

In the health area, Australia has the fundamental National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) and the applied Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) to span the discovery-translation-applied-commercialisation pipeline. At present no such mechanism exists for other disciplines across these two spectrums.

Such a fund would rely on and facilitate three priorities: the necessary people skills, connections and culture, the ideas driven by research and flowing into a collaborative risk-managed environment and the patient capital to translate, commercialise and apply research in areas crucial to our country’s well-being.

In addition to excellent research and industry know-how, the fund would build on several bases: industry incentivised by the RDTI,, successful programs for building skills (e.g. ARC Industrial Transformation Research Program) that could be scaled up, programs such as the Industry Growth Centres and Rural Research and Development Corporations (RDCs) demonstrating that sectoral approaches can be highly successful, and research infrastructure including NCRIS facilities that are often the basis for precincts and collaboration.

The concept of the fund is to implement a comprehensive model that systemises the effort to:

- Drive awareness and absorptive capacity and skills of industry to take on ideas available to them.

- Foster a strong mutual understanding by industry and academia of each other’s sectors, supply chains and capability.

- Build skills by embedding people from industry and academia in each other’s organisations, thereby also building the ability to absorb the ideas and technology being translated.

- Develop and strengthen an entrepreneurial culture in our research community spanning undergraduate, post-doctoral and early career researchers.

- Expand the cohort of translational brokers – those people that have the skills to relay from academic to industry and vice versa – who know the opportunities that exist and how to capitalise on them.

- Fund early-stage R&D translation, where the highest risks are, while also supporting venture capital investments into promising research discoveries and assist in their commercialisation on the right hand of the translation spectrum.

The Go8 does not at this point advocate specific funding sources or a quantum of funding, although Go8 members are individually advancing potentially workable and detailed proposals that elaborate upon the intentions above. Crucially, the fund would create a compounding effect of investment into new additional dollars for translation and be a shared model, ensuring that the commercial benefit of any research outputs both privatises profit and is redirected to sustainably support further rounds of partnership funding.

Specific remarks on the consultation paper

The Go8 broadly concurs with the following approaches suggested in the consultation paper:

- The need to understand and activate those incentives that prompt business and university participation in research commercialisation. In addition, it should also be acknowledged that ‘bottlenecks’ will occur, once the research base is enhanced to be entrepreneurial and incentivised industry in place, without an expansion of the resources and experience to drive commercialisation as a professional skill and service. Third stream funding could assist with expanding such tech transfer and commercialisation capability.

- The Go8’s 2020 blueprint Enabling Australia’s Economic Recovery through Supporting Research Excellence recommended the concentration of sustainable translation across national priority areas – including those areas in which we have leading edge capability; that are essential to the national fabric; where we can foster emerging industries; cannot afford to fall behind; and those whose future relies on digital or technological reform. A mission-based approach would ensure this.

- The further exploration of skills gaps[13] in both universities and business that need to be rectified for research commercialisation to scale up, including skills to foster understanding between universities and businesses, as well as innovation and industry facing skills in researchers. Initiatives should be implemented over sufficient time and with enough incentives to enable generational change. We need to increase the numbers of skilled people and establish new skillsets.

- The need to increase collaboration between university researchers and transfer of knowledge to industry and especially SMEs, built on a refined understanding of the motivations, concerns, attitudes to risk and resources required.

- It is simplistic to suggest that SMEs know they must innovate but have insufficient access to university knowledge. Go8 experience shows that what often motivates resource and time-poor SMEs to work with universities is having a quality relationship with people and teams rather than IP portfolios.

- The key is to establish how universities can adapt their usual modes of engagement to attract SMEs, alongside what due diligence SMEs should undertake, and what third party intermediary assistance is needed. While exemplar overseas initiatives exist for raising SME absorptive capacity (such as the UK Knowledge Transfer Partnerships), we cannot discount and instead should scale domestic programs such as the CRC-P schemes that also drive this as well as focus on workforce mobility measures to enhance the permeability between universities and industry.

- The Go8 supports greater systemic focus on and is working towards improved recognition of and reward mechanisms to support university personnel translating their research and engaging with industry. More recognition is needed that the risk is not just to business, and that greater commercialisation by university entails as much of a personal and professional adjustment by academics as it does for business owners.

- The stage-gated approach to designing a scheme, that also acknowledges the importance of having viable ideas, effectively validated, to flow through to the start of the commercialisation continuum. There is simply insufficient proof-of-concept support to enable the testing, prototyping, and confirmation of new discoveries to increase investors and industry’s confidence, as this stage is currently largely enabled by university discretionary funding (in part drawn from international student income).

The Go8’s recommended process of co-design and the ongoing committee goes to the governance questions posed in the paper. A collective effort is needed – one that promotes and reinforces positive collaboration between industry and universities.

Finally, any model developed to advance university research commercialisation must be a long-term sustainable approach if it is to progress Australia beyond the current levels. It is no coincidence that many nations’ comparative success touted in the discussion paper is due to their long-standing national commitments, which must be emulated here[14].

Yours sincerely

VICKI THOMSON

CHIEF EXECUTIVE

Appendix: SCOPR 2019 – Go8 summary commercialisation outcomes and share of total outcomes

Survey of Commercial Outcomes from Public Research (SCOPR) collects data from 49 Australian and New Zealand universities, medical research institutes and publicly funded research agencies. It enables national and international benchmarking of respondents and helps to inform decisions by research organisations, government and industry stakeholders seeking to enhance industry engagement and research commercialisation.

Table: Institutional responses to the Survey of Commercial Outcomes from Public Research (SCOPR) – 2019 data

SCOPR[15]

The inaugural SCOPR conducted by Knowledge Commercialisation Australasia (KCA) covers the calendar years 2017, 2018 and 2019. Forty-nine institutions including 34 Australian (of which 24 were universities) and 15 New Zealand research organisations responded to the survey.

The SCOPR report[16] published in 2020, charts institutional responses to the survey as per the above table.

SCOPR Measures

An invention disclosure describes an invention in detail and is used to determine its creators, novelty and potential for social impact and/or commercialisation.

A patent grants an inventor exclusive rights to the IP for a designated period in exchange for a comprehensive disclosure of the invention. Non-patented IP includes plant breeders’ rights, confidential know-how, registered designs, circuit layouts, trade secrets, software, trademarks, apps etc.

Licences, Options and Assignments (LOAs): Licences may grant another party (licensee) the rights to make/sell/ use the IP owned by the licensor. Options grant the potential licensee time to evaluate the IP and negotiate the terms of a licence agreement. Assignments convey all rights and title to, and interest in, the licensed IP to the assignee.

Spin-out and startup companies are founded through licensing or assignment of IP. Spin-outs are launched by the research organisation. Start-ups are launched by other parties through licensing or assignment of IP.

Commercialisation revenue is gross income from all LOAs, material transfers and sales of

products or services based on expertise or IP, plus cashed-in equity, minus any

cost of acquiring the equity. (Excluded: research funding, copyright income,

non-cash value exchanged for equity holdings, value of equity not cashed-in,

patent expense reimbursement, consultancies and contract research – unless or

until new IP is created.)

[1] Data from the Survey of Commercial Outcomes from Public Research (SCOPR) conducted by Knowledge Commercialisation Australia (KCA): https://techtransfer.org.au/metrics-data/

[2] IISA in 2021 recommended investment in basic research does not fall given its importance to future commercial opportunities (https://www.industry.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-01/gov_investment_in_innovation_science_and_research.pdf)

[3] “Biden Pursues Giant Boost for Research Funding”, Nature, 9 April 2021, https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-00897-0

[4] Businesses with 0-19 employees make up 97% of all businesses in Australia (ABS 2021, Counts of Australian Businesses). An earlier ABS survey (2020, Characteristics of Australian Business) found that around 36% of businesses in this size range introduced or implemented any innovation. Only 2.1% of innovating businesses in this size range accessed ideas or information for innovation from universities or higher education institutions (ABS 2020, Characteristics of Australian Business).

[5] Lessons may be drawn in how this occurs from precincts surrounding UK and US universities – e.g. Cambridge UK and software & MIT and the Porter model – where SMEs are early adopters and Beta sites for testing new tech, products and services that then are exported into global markets when they have been optimised and their manufacture scaled.

[6] As an example, it took 15 years for Gardasil to be commercialised: https://uniquest.com.au/impact_stories/a-global-solution-to-eradicating-cervical-cancer/

[7] See https://uniquest.com.au/industry-impact/

[8] https://techtransfer.org.au/landmark-survey-highlights-pathway-to-building-next-cochlear-and-csl/

[9] Further detail can be found in Go8 capability statements on space, defence, genomics and AI and Go8 research blueprint, or can be provided on request

[10] For example, https://melbconnect.com.au/

[11] https://www.industry.gov.au/policies-and-initiatives/promoting-innovation-precincts

[12] https://go8.edu.au/research-infrastructure-funding-a-win-but-rd-tax-incentive-an-economic-opportunity-missed

[13] For example, this is discussed for the medical technology, biotechnology, pharmaceutical and digital health (MTP) sector at https://www.mtpconnect.org.au/reports/redi-skills-gap

[14] The United States Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) was established in 1982 while the Canadian industrial research assistance program began in the 1950s.

[15] https://techtransfer.org.au/metrics-data/

[16] https://techtransfer.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/SCOPR-REPORT-FINAL-for-web.pdf