May 20, 2021

Department of Education, Skills and Employment

By Email

Introduction

The Group of Eight (Go8) welcomes the opportunity to contribute to the development of Australia’s Strategy for International Education 2021-2030.

Please note this submission represents the views of the Go8 which leads policy and advocacy for Australia’s consistently leading-research intensive universities with seven of its members ranked, again consistently, in the world’s top 100 leading universities. Each member Go8 university may submit its own related submission.

Also note that the Go8 is happy for this submission to be published and does not wish any of it to be treated as confidential.

In developing our response, the Go8 sought advice from a wide range of industry stakeholders on the basis that there are many sectors of the economy with ‘skin in the game’ in ensuring Australia continues to have a robust, resilient and quality international education sector.

As noted by one of the participants at a Go8 industry consultation session: “Australian universities are an amazing success story… we have some of the best universities in the world, we are churning out amazing high-quality research, and we have created [the] third biggest export industry”.[1]

Together we agreed upon a set of principles that we believe should guide the development of the nation’s international education strategy and these principles underpin our submission.

Executive Summary

The Go8 universities have been a key part of the success of our international education sector. We educate 150,000 international students on and offshore. Pre-COVID, these students contributed almost $18billion each year to the nation’s education exports and supported more than 73,000 jobs in Australia. The economic impact is obvious and essential to our post pandemic recovery.

This submission is not intended to rehearse these arguments. The value of international education to the economy, to society, to the national workforce and to Australia’s capacity to engage effectively in global research is well known. The Minister for Education, the Hon Alan Tudge MP, noted recently that the sector had added $37.5 billion to the economy last financial year and is estimated by his own Department to support 250,000 jobs. [2]

Instead, the Go8 has chosen in this submission to take a broader perspective.

The fact is, that in the immediate post-2020 environment, in which COVID-19 remains a challenge and in a shifting geo-political context with the capacity for rapid change, all sectors – including international education – need to adapt. But this must not happen in isolation. Universities in the 21st century are not ivory towers. Instead, they operate within a local, national and global context to serve the needs and boost the prosperity of the whole society, which in turn relies on the research and graduates that universities such as the Go8 provide.

Through their everyday activities, Go8 universities:

- Provide employment and support the economy of the immediate community in which we are based;

- Produce a pipeline of talent to support Australian industry activities whether on or offshore;

- Populate the international workforce with Australian alumni who can foster ongoing relationships, facilitate opportunities for Australian industry offshore and promote Australian values to a global audience; and

- Ensure a pipeline of research outcomes that fuel commercialisation, improve the quality of Australian life, support the development of new industries and help keep existing industries at the cutting edge.

Indeed, many of the priority measures highlighted in the 2021 Budget demonstrate the significance of high-quality universities to the national prosperity. Universities will be critical to efforts to boost responses to mental health, aged care and digital transformation, and driving medtech and biotech innovation.

For this reason, the Go8 has prepared this submission in consultation with a number of industry stakeholders to inform an approach that reflects not only our own concerns, but those of our industry partners.

The recommendations and principles presented here are not for the benefit of universities alone, but intended to outline how universities, industry and government can and must work in partnership to support the transformation of our economy to deliver success for Australia in a new operating reality.

Those individuals and organisations that contributed to the principles and recommendations presented in this paper are listed in the Appendix. We thank them for their contribution. The quotes included in the paper are not attributed according to Chatham House rules, but were made by industry participants at these sessions.

Key Principles to Underpin Australia’s International Education Strategy

- International engagement is essential to the development of Australia’s sovereign capability and economic competitiveness and international education is a key plank in Australia’s international engagement.

- International education and research should be leveraged to drive Australia’s economic interests through sovereign capability building and an enhanced domestic workforce.

- International education and research should be leveraged to pursue Australia’s geopolitical interests and to contribute to the region.

- Australia should identify and build on its competitive advantages in international education in a post-COVID world.

- In order to fully realise the potential of international education and research, both Government and the Australian community should have a deeper understanding of its value to Australia.

Recommendations for Australia’s International Education Strategy

- An Australian International Education Strategy must focus on what is needed to build Australia’s sovereign capability and position the nation for success in a knowledge and technology-driven world. International engagement in research – including the fostering of international talent by high performing research-intensive universities – must be a key pillar of this strategy.

- The international education sector must be viewed as a key pillar of our national foreign policy and defence sector strategies to build multi-lateral alliances across the Indo Pacific region and promote perceptions of Australia as a trusted regional partner.

- The International Education Strategy should leverage our capacity to deliver high quality research training to take advantage of the Asia-Pacific becoming the centre of mass for large government and industry investment in R&D.

- Australia should build on its competitive advantages in high quality research and postgraduate training to attract and retain high quality talent into the country to ensure a pipeline of skills into areas of key industry need.

- Australia should develop targeted migration pathways in areas of key need and should also seek to use the talents and capabilities of our international student cohorts to address current gaps in Asian language and cultural capabilities.

- The Strategy should look to maximise opportunities to encourage work integrated learning projects and internships, including incentives for participation, to maximise both the Australian education experience and opportunities to harness international talent for the benefit of the Australian economy;

- Industry, government and the sector need to invest in promoting the strategic value and extensive advantages of international education to the broader Australian community.

Response to the Terms of Reference

What are the Key Priorities for a new Australian Strategy for International Education?

The Go8 supports the Government in the decision to use this strategy to take a longer-term view. This is not to dismiss the considerable challenges facing the sector in the short term, nor to ignore the imperative for government, industry and universities to work together to address them. However, the considerable changes in the environment mean it is unlikely and unwise to assume resumption of business as usual once our borders re-open. It is therefore prudent to consider what is achievable and desirable by 2030 to ensure that our nation is positioned for success, rather than be driven solely by short term need.

As noted above, the Go8 – in consultation with key industry stakeholders – developed a set of principles that we collectively believe should underpin the new strategy. These are listed and explored below as the key priorities that should help to drive broader benefit to the nation, rather than just assist the sector. Where relevant, further detail is provided in our responses to the additional terms of reference.

- International engagement is essential to the development of Australia’s sovereign capability and economic competitiveness. International education is a key plank in Australia’s international engagement.

The drivers of prosperity are shifting. Success is increasingly driven by knowledge and discovery, which form the foundations of technological understanding and progress. This in turn is driving an aggressive and competitive race for talent as developed economies realise the imperative to ensure they are not disadvantaged within this new operating reality.

As we have seen in the fields of cybersecurity, artificial intelligence, and the race to counter COVID-19, it is no longer sufficient to have a talent base that is strong by national standards; it is the international benchmarks of research and technological excellence that will increasingly matter.

As noted in a 2019 letter to President Trump from 50 deans from top US business schools and CEOs from leading companies, even the United States – with a population orders of magnitude larger than Australia’s – does not have a sufficient supply of the high-skill talent it needs, nor the capacity to train enough people. Without an inflow of talented international students and skilled immigration, “this deficit of skills in key fields will hinder economic growth”.[3]

Canada has also recognised this need. In January of this year Marco Mendicino, Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship, announced polices designed to encourage the retention of international graduates to ensure that “Canada meets the urgent needs of our economy for today and tomorrow”. [4] And the UK’s Research and Development Roadmap seeks to “send a powerful signal to talented people around the world: come to the UK”.[5]

Australia, like the US, Canada and the UK, cannot rely on growing our own. The reality is that we do not – and will not – have sufficient domestic capability to fulfill these needs. This is particularly acute in areas such as ICT. This includes areas such as Artificial Intelligence, Cybersecurity, the Internet of Things and the general digitisation agenda. This means that our goal of sovereign capability and resilience will not be achieved if we cannot draw on a global talent pool.

While there are certainly opportunities for Australian education providers to engage in delivery modes offshore, and these should be explored, they cannot replace the onshore cohorts that provide an ongoing talent pool to address industry needs.

| “To recruit local engineers here in Australia… to be very blunt and transparent we are struggling. The reason why we are struggling is that we are looking for some skills and we don’t find them. So sometimes we have to recruit from the UK or other countries… but this is a challenge that we have to address”. Go8 industry consultation session on international education |

It is in this context that the Go8 suggests that Australia’s strategic goal over the next decade should not be an attempt to return to a pre-COVID status quo, regardless of whether that is even feasible. Rather, it should be to ensure that our nation can access the necessary flow of talent to support the kind of prosperous, engaged and sovereign nation that will be a pre-requisite for success in the coming years and decades.

To fail to do this is to condemn Australia to increasing disengagement and irrelevance on the world stage.

- International education should be leveraged to drive Australia’s economic interests through sovereign capability building and an enhanced domestic workforce.

As noted by participants in the Go8 industry consultations, and for the reasons outlined above, international engagement is a key pillar of boosting Australia’s sovereign capability and economic competitiveness, by building strategic relationships with key partners, supplementing domestic development opportunities and facilitating access to the global talent pool.

Access to globally in demand skills (e.g. AI, quantum computing, digitisation) is not just critical to the ICT sector, but will underpin the viability of all sectors over the coming years. Building these skills to a cutting-edge level is therefore fundamental to Australia’s economic prosperity.

| “The government is very focused on investing in our sovereign capability, but our sovereign capability can’t occur if we’re not part of the global pool of talent”. “Be[ing] removed from the global pool of talent… is the biggest risk we face here long term”. Go8 industry consultation session on international education |

Demand for a highly-skilled workforce in the health and aged care sectors is increasing and it is important to note a 2019 Deloitte finding that “the interpersonal and creative roles, with uniquely human skills like creativity, customer service, care for others and collaboration” will be the hardest to automate.[6]These skills are also strengthened through international engagement, which helps to build dynamic, up to date, competitive and exciting workplaces that not only attract the best talent to work in Australia but are critical in the retention of domestic talent that is vulnerable to being recruited offshore.

If we do not plan appropriately, Australia could be caught in a vicious cycle, where disengagement from the international exchanges that fuel development and discovery not only discourages new talent from coming to Australia but sees home grown individuals lured to live and work in more exciting, engaged, dynamic and lucrative economies.

And that intercultural competency starts in our world class universities. Around 160 nations were represented across the Go8 in 2020, and while this level of diversity may not be sustainable in a post-COVID context, the ability for our domestic students to develop their skills base in a diverse setting should not be discounted.

| “There is absolutely no doubt from a business point of view, and even from a migration policy and economic policy point of view… what better way for an industry to contribute to the future skills of Australia by encouraging people to come here, study, do our qualifications and then be available for employment and sponsorship within the country, having not cost Australia anything for all of their primary, secondary and tertiary education”. Go8 industry consultation session on international education |

- International education should be leveraged to pursue Australia’s geopolitical interests and to contribute to the region.

Australia has a key advantage in our location within the Indo-Pacific region, which is shifting to become the centre of economic and geostrategic power. This provides a rare opportunity to boost our influence across the region by:

- Taking a more strategic approach to international education to seal our reputation as a provider of high-quality education within the region, especially in postgraduate and research delivery (see below);

- Boosting our soft power through returning graduates and building our alumni base; and

- Supporting perceptions of Australia as a trusted regional partner.

All of the above are key to supporting our current foreign policy and defence strategies of building and cementing our multi-lateral alliances across the Indo-Pacific.

Having an onshore talent pool of international students also provides Australia with an immediate solution to an area of known need. A cohort of native Asian language speakers bring with them cultural capabilities that can be leveraged to the advantage of Australian industry and will increasingly be a critical asset in the current geostrategic context. It also helps to build domestic students’ capacities in multicultural environments.

- Australia should identify and build on its competitive advantages in international education in a post-COVID world.

Through this strategy, Australia should take a clear and objective view of our competitive advantages in a changed and more aggressive global marketplace for students and reiterate our value proposition to attract the best and brightest to build their careers to Australia’s national advantage.

Table 1 below shows the growth in higher education enrolments by level of study over the five years from 2016 to 2020. It clearly shows growth at the postgraduate level (incorporating both coursework and research programs) has accounted for 63% of the growth at Go8 universities, and 51% for the sector overall.

Table 1: International Enrolments at Postgraduate Level (coursework and research), December YTD

December YTD, Higher Education, Postgraduate

| Change | Change | |||

| 2016 | 2020 | n | % | |

| Go8 | 56,249 | 91,824 | 35,575 | 63.2 |

| All Australia | 143,927 | 217,020 | 73,093 | 50.8 |

| Total | 200,176 | 308,844 | 108,688 | 54.3 |

Source: AEI

This is a golden opportunity for Australia. Postgraduate education delivers graduates at the higher skills and capability end, and research-capable graduates are able to drive the discoveries on which industry will increasingly rely.

This need came through clearly in the Go8 industry consultations. It was noted that the Asia-Pacific is becoming the centre of mass for large government and industry investment in R&D and if Australia is smart, we can build on our already strong research capacity to use this to our advantage.

There are also considerations around sovereign capability. In the 21st century, research and sovereign capability are inextricably linked. Australia will not be able to progress its sovereign capability agenda without a strong research sector. And international engagement – including international research students – is a key pillar of our research sector. Indeed, recognition of the need for seeding of Australia’s knowledge base with international expertise has been recognised by the Government in the development of its Global Talent Visa, designed to provide a streamlined pathway for highly skilled professionals into Australia.

Australia, by harnessing the collaborative capacity of universities, industry and government, should look to leverage extensive networks established through international education and research to take advantage of this growth for the benefit of our nation and the region.

Using our strengths in research and postgraduate education delivery to target high-achieving international students in identified strategic areas will build both workforce capacity and quality for Australia, as well as provide an enhanced learning environment for domestic students. This includes boosting our research commercialisation capacity, as we bring in the entrepreneurial talent necessary to achieve this goal. In the US, for example, immigrants make up only 15% of the workforce, but comprise close to a quarter of all entrepreneurs and inventors.[7]

Consideration should be given to facilitating short or long-term migration outcomes for high-achieving students in key disciplines. Other graduates could become a valuable resource for Australian companies looking to employ native speakers in their home countries or contribute to Australia’s soft power at a time of geostrategic stress.

| “We need a policy setting that gives foreign students a pathway to residency again. Because there is a general discussion on the street that says if you bring in good quality people from overseas and they actually can’t stay then you are actually just serving a purpose for someone else. I don’t think that’s been said enough”. Go8 industry consultation session on international education |

- In order to fully realise the potential of international education, both Government and the Australian community should have a deeper understanding of its value to Australia.

There is no doubt that Australia must do better at explaining the strategic value and extensive advantages of international education to the broader Australian community.

First, we need a clear vision of our competitive advantage in an international education market in a world where other countries are seeking to erode Australia’s market share.

Second, we need advocates from across the Australian experience to explain the value of a deeply engaged society, including the role of international students. This may require filling data gaps to create a more comprehensive and nuanced picture of the international education sector across industry, government, small business, community organisations as well as higher education. It should go beyond just the economic, to demonstrate a more complete and comprehensive picture across all areas of society.

The Go8 would be happy to work with Government and industry to determine what additional data may be required to assist in this process, and to engage with other groups as appropriate to design a communication strategy.

Students should be at the centre of the new Strategy. How can Australian education providers deliver the best possible student experience both now and in the future?

The Go8 agrees that offering a strong student experience is a key attractor for the industry.

Strong enrolment growth in the sector over the last decade would suggest that the experience offered pre-COVID was extremely attractive to the international community. However, consideration of how to strengthen the experience in line with new strategic directions could help to underpin the ongoing attractiveness of an Australian education in a new era of competition.

As noted above, Australia has the opportunity to focus particularly on postgraduate and research education. This would have a number of advantages – delivering a pool of global talent in areas of key need; fostering Australia’s capacity to commercialise research discoveries; and creating a dynamic, quality environment which would in turn attract foster more industry engagement. DESE data shows that over half of international enrolments at Go8 universities (57%) are at postgraduate or Higher Degree Research (HDR) level, demonstrating considerable demand at higher levels.[8]

Indeed, some sectors – such as our burgeoning defence and space industries – are looking for exactly this mix of high-quality research capability, connection to global supply chains and geography that offers clear skies, low noise and light interference, all located within a key global region.[9] Australia could build on existing alliances to develop fast-track processes to facilitate exchanges of postgraduate students and academics in these key areas, helping us offer a truly engaging international and domestic education experience while addressing key needs of strategically important industries.

Internships are one way that postgraduate and research skills could be developed and harnessed to the value of business and developed to enrich the experience of the student.

However, current conditions expose businesses to risk from uncertain industrial relations requirements. Addressing this issue could bring multiple benefits, eg:

- Improving the student experience for both domestic and international students by providing workplace exposure during postgraduate and research studies.

- Providing industry with opportunities to engage with the talent pool of students in key areas of workforce need.

- Encourage more students to study in key areas by providing greater experience and workplace opportunities.

Government, industry and universities could work together to overcome the regulatory barriers employers face in employing interns and to design attractive internship programs that provide students with valuable workplace engagement opportunities and provide employers opportunities to meet needs such as language skills, and future recruitment opportunities.

It would also allow Australia to market its educational offerings as engaged and industry relevant, and could increase the potential for a pipeline of commercialisation of PhD research findings when developed in conjunction with an industry partner.

| “In the French system it is quite easy to have access to a large number of interns for three months, six months, up to even a year, we train these students and then they come back to us and we can recruit them.” Go8 industry consultation session on international education |

What changes are needed to make Australia more globally competitive over the next decade?

As we note as one of our key principles, Australia should identify and build on its competitive advantages in international education in a post-COVID world, and there is a prime opportunity for us to position ourselves in the postgraduate and research space.

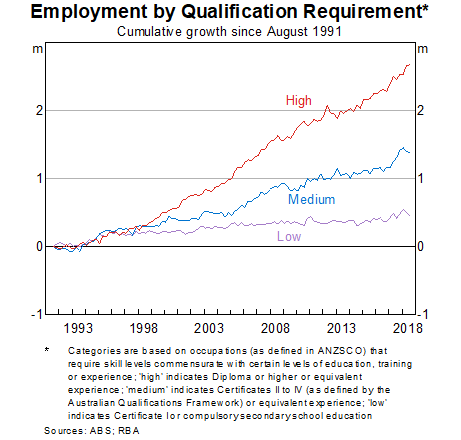

Over the last 30 years the Australian economy has become increasingly sophisticated in terms of the qualifications required by employers with the largest growth in higher education qualifications.

This evolution continues with many key industries increasingly relying on a postgraduate qualified workforce.

The Deloitte report ACS Australia’s Digital Pulse: Future directions for Australia’s Technology workforce 2021[10] estimates that between 2020 and 2026 postgraduate qualifications will be the fastest growing qualification requirement in the technology sector, growing at an average rate of 6.7% per year with a total increase in postgraduate workforce of 122,000 over this period.

In 2019 there were only 1,900 domestic completions in IT degrees at the postgraduate level with 36% of these at Go8 institutions.[11] It is clear this will not be sufficient to fuel our growing Australian industry needs.

Australia also needs an ongoing flow of talent to ensure that our own skill base remains up to date and relevant against global knowledge standards. Up until now, Australia has benefited greatly from this exchange.

Across the Go8 universities in 2020, staff born overseas comprised around 34% of the total workforce. Former Australians of the Year Professor Ian Frazer AC (University of Queensland, born in the UK), Professor Fiona Wood AM (University of Western Australia, born in the UK), Professor Patrick McGorry AO (University of Melbourne, born in Ireland) and Professor Michelle Simmons AO (University of New South Wales, born in the UK) have all used their skills and talents to the benefit of this nation, rather than the one of their birth.

Furthermore, international PhD students contribute a sizeable quantum

to Australia’s national research effort. Data provided by the Department of

Education show that, in 2019 (most recent year), international students

comprised around 38% of the total PhD student cohort, and well over half in key

discipline areas (59% in Information Technology and 62% in Engineering and

Related Technologies).[12]

Shutting off this flow of international talent will further disadvantage an

Australian industry which is already struggling to find enough local talent to

fuel its needs.

Australia also requires a transition plan that recognises the current impact of closed borders on both the international education sector and the broader economy. This is part of allowing business and industry – as well as the international education sector itself – to plan effectively for when the health conditions are able to allow the return of students onshore.

| “[We] can’t wait until the magic wand fixes the pandemic, and then start upscaling the numbers of people that come over the border. We do need to have a plan for growth now”. Go8 industry consultation session on international education |

How do we create a uniquely Australian education experience?

As we note as one of our key principles, Australia should identify and build on its competitive advantages in international education in a post-COVID world.

Australia needs to have a clear vision of its competitive advantage in an international education market in a world where other countries are seeking to erode Australia’s market share.

Communicating the full value of international education requires filling data gaps to create a more comprehensive and nuanced picture of the international education sector. This includes in which disciplines and at what level international students are studying, the link to commercialisation outcomes of research undertaken by international PhD students, and the economic value of this activity to Australia.

Once we have this complete picture, we can design programmes and opportunities that emphasise these strengths. For example, there are opportunities to establish Australia as a Centre of Research Excellence for international business in critical areas (e.g. defence research). However, such companies rely on a pipeline of high-quality Australian research in the presence of international engagement to ensure they remain competitive and at the cutting edge.

There are also

opportunities to offer a unique training experience for medical and health

professionals. For example, Australia has a strong need for more medical and

health professionals operating in the regions. This results in significantly

worse health outcomes in rural and regional areas compared to metropolitan. Yet

rural practice offers opportunities to be able to perform to a high standard

across a range of areas: primary care, critical care, emergency care, etc,

producing attractive and highly skilled graduates. This could be positioned as an attractor into rural practice in Australia, for both domestic

and international students.

The Go8 looks forward to being involved in further consultations about this important strategic area. We welcome any further opportunities to contribute to this important process.

Yours sincerely

VICKI THOMSON

CHIEF EXECUTIVE

Appendix: Participants in Go8 industry consultation sessions on international education

The following organisations took part in the Go8 industry consultation sessions, which informed the creation of this submission:

- Asia Society

- Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (ACCI)

- Australian information Industry Association (AIIA)

- CRC Association

- McKell Institute

- Naval Group Pacific

- Office of the Chief Scientist of Australia

- Property Council of Australia

- Rural Doctors Association of Australia

- Siemens Australia

[1] Consultation session, 4 May 2021.

[2] https://ministers.dese.gov.au/tudge/challenges-and-opportunities-international-education

[3] https://www.gmac.com/-/media/files/gmac/research/talent-mobility/gmac-public-letter-b-schools.pdf

[4] https://thepienews.com/news/canada-expands-pathway-residency/?mc_cid=259ddf0243&mc_eid=670ca82f40

[5] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-research-and-development-roadmap/uk-research-and-development-roadmap

[6] https://www2.deloitte.com/au/en/pages/media-releases/articles/work-human-australia-faces-major-skills-crisis-120619.html

[7] https://www.forbes.com/sites/adigaskell/2019/12/17/why-immigration-is-so-important-in-the-global-race-for-talent/?sh=79ff10c41022

[8] AEI data for full year 2020 (Dec YTD).

[9] https://www.industry.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-03/australian_space_industry_capability_-_a_review.pdf

[10] https://www2.deloitte.com/au/en/pages/economics/articles/australias-digital-pulse.html

[11] DESE uCube http://highereducationstatistics.education.gov.au/

[12] DESE Higher Education Statistics Collection, Full year 2019