April 15, 2025

Robyn Denholm, Chair, Strategic Examination of Research and Development (SERD) Panel, C/O SERD Secretariat

Group of Eight Universities (Go8) submission to the Strategic Examination of Research and Development (SERD)

The Go8 consents to the publication of this submission and has no wish for any of it to be treated as confidential.

Introduction

Go8 universities are the research powerhouses of Australia, responsible for over 20 per cent of Australia’s research and development (R&D) investment. This equates to $8.5 billion in annual terms and is approximately equal to the combined investment in R&D by Australian governments and the rest of the higher education sector in Australia.

To further put into perspective that contribution from just eight universities, the investment represents about 0.37 per cent of Australia’s GDP. In 2021, this was an equivalent share to the entire contribution of the United States higher education sector to US R&D investment as a percentage of US GDP. Importantly, as well as quantity, our research is underpinned by quality, with 93 per cent of our research rated above or well above world standard by the Australian Research Council.

Go8 members also produce more research commercialisation revenue than the CSIRO and are comparable to leading US institutions in this respect. Australia’s higher education sector undertakes more applied research and experimental development – as a percentage of GDP – than universities in other innovative economies.

We make these points to emphasise the importance of the Go8 members in Australia’s R&D system and to highlight that Go8 members already undertake a significant amount of applied research and commercialisation and are continually striving to do more.

Without this critical investment, Australia would not be a modern knowledge-based economy, and we would become mediocre at seizing national opportunities and meeting challenges that impact the everyday lives of Australians.

We need a national strategy and roadmap of reforms

Australia is falling behind globally on the critical investment that R&D represents, and if we do not turn it around, we will simply be a poorer nation. Our recommendations start with setting a clear national purpose and direction – that is, the Australian Government should formally adopt a national R&D investment target of reaching 3 per cent of GDP by 2035.

A national target on R&D is supported by the Australian Universities Accord Review Panel (2024) who recommend the Australian Government:

“Develop a multi-agency government strategy that sets medium and long-term targets for Australia’s overall national spending on R&D as a percentage of GDP, requiring a significant increase to ensure Australia fully utilises the potential of its research sector and, consequently, competes more effectively in the global knowledge economy”.[1]

The Go8 has developed a roadmap of policy reforms to lift R&D intensity in Australia to a target of 3 per cent of GDP by 2035. The following are our recommendations to the SERD Panel and, in turn, the Australian Government.

The roadmap of reforms we recommend is centered on lifting business R&D. This is because as much as the Go8 leads Australia’s research capacity, we need a lift in overall R&D intensity (R&D investment as a percentage of GDP), requiring the business sector, which contributes approximately 50 per cent of Australia’s R&D investment, to lift its intensity.

As a nation, lifting R&D intensity also requires improved university-business collaboration and, importantly, the Australian Government to address existing policy shortcomings with respect to facilitating both business and higher education sector R&D.

Go8 recommendations to the Australian Government

A national R&D target with measurement and coordination of its achievement

- Formally adopt and implement a national R&D investment target of reaching 3 per cent of GDP by 2035 and adopt a roadmap of reforms to achieve the target.

- Establishment of a single National Agency for Research & Innovation for a whole of government approach to managing policy and funding for research and innovation. This new agency would develop and have the carriage to implement a national research strategy (informed by the outcomes of the SERD) towards a national R&D target.

- The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) should survey and report annually on R&D (expenditure) investment for every sector of the economy, so we can better measure national progress.

Consistent Australian Government research procurement policy

- Implement a consistent procurement policy where the Australian Government provides, as a transitional measure, at least 50 cents in the dollar of indirect cost support for all research procured.

Full economic cost of government research grants

- Develop and implement a policy to provide the full economic cost of government research grants within a decade.

Strengthening linkages between industry, universities and government and promoting translation of research

- Establish national doctoral training centres that align with all key sectors of Australian economy and society and in areas of national priority.

- Build on the current Business Research and Innovation Initiative (BRII) program under the Industry, Science, and Resources portfolio by introducing a Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) type program to incentivise SMEs to engage with Australian research institutions on R&D collaboration.

- Clear and equitable strategies need to be developed by the Australian Government in partnership with universities and industry to promote and incentivise appropriate transfer and use of university IP, particularly in key identified areas of sovereign need or national strength, where the retention or majority control of that IP in-country supports national economic, social and other goals. These must however be matched by the investment to test (including via proof of concept) and commercialise such IP, as well as support for local capacity to develop, produce and manufacture the resulting technology or solution, and continued openness to trade ideas with like-minded partners.

- The Australian Government reject any proposed overhaul of research-industry IP arrangements aimed at removing university institutions’ and creators’ rights to own the IP and shifting these rights wholescale to industry, or at diminishing the controls that the university creators have through a reduction of licensing arrangements.

- Boost the effectiveness of the Higher Education Research Commercialisation Intellectual Property Framework by revising the template agreements provisions to address inappropriate liability provisions and unreasonable intellectual property indemnities for universities as public institutions. Maintain these agreements as voluntary to use.

Maximising the value of existing investment in R&D and driving greater R&D investment by industry

- Leverage the Research and Development Tax Incentive (R&DTI) by offering an additional equity or debt finance incentive from the National Reconstruction Fund (NRF) to businesses that qualify for the R&DTI and enter into formal R&D collaboration with an Australian research institution.

Skilled migration and investing in Australia’s domestic research workforce

- Boost Australia’s R&D workforce through skilled migration:

- Under the new Skills in Demand visa as part of the Migration Strategy, provide direct and expedited permanent residency for international students obtaining a PhD at an Australian university in areas of identified critical need.

- Through the new National Innovation visa, develop a national strategy to actively attract and retain high-quality international researchers.

- Further invest in the domestic R&D workforce by:

- Prioritising reforming university funding rates and levels for STEM related fields of education to raise STEM supply through universities.

- Ensuring stipends and scholarships for higher degree by research students are attractive to retain and grow the pool of researchers in Australia.

Elevating Indigenous peoples in our R&D system

- Continue to develop measures to protect Indigenous knowledge by implementing Indigenous data sovereignty and protection of Indigenous cultural and intellectual property.

Pursuing global R&D partnerships

- Pursue Australia’s participation in globally leading-edge research consortia and collaborations such as Horizon Europe.

Access to (private) finance for R&D

- Facilitate the presence of additional intermediaries and aggregators (between superannuation funds as investors and early-stage enterprises as investees) to encourage R&D.

Sustainable national research infrastructure

- Facilitate sustainable national research infrastructure by moving the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy program to a future fund style of funding and, in collaboration with State Governments and universities, undertake a comprehensive review of governance and administration of the program and existing funded facilities.

A macroeconomic environment conducive for domestic R&D and innovation

- Continue to pursue an open trading system, including reducing non-tariff barriers to trade in services and also pursue competition reforms to rebuild the momentum of a dynamic economy.

Mission-oriented policies

- Establish a fund similar in scale to the Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) focused on fields of research outside of the MRFF.

Innovation hubs supporting knowledge sharing and transfer

- Work with States/Territories and local government to coordinate existing programs and support to incentivise development of knowledge precincts through co-location of Australian universities and businesses. The Monash University-Moderna initiative is an example.

Open access to research

- Implement open access to research principally funded by the Australian Government in a way that does not result in extraction of rents by publishers from researchers and readers but acts to increase knowledge available to businesses and improve diffusion of knowledge.

Redressing the mischaracterisation of basic research and reversing the spending drop

- Ensure sustainable increased funding for basic research, both in the higher education sector and in industry sectors that rely on it.

Contributions and advice in the development of our roadmap of recommendations have been provided by:

- The Go8 Project Advisory Group: Professor Emma Johnston AO, University of Melbourne, and Dr Dean Moss, University of Queensland.

- Standing Go8 Committees with experts in research, innovation and commercialisation, and the Go8 Economics Advisory Group consisting of leading economists across the Go8 universities.

- Workshops and discussions with business groups including the Business Council of Australia, the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry (ACCI), Ai Group, the Council of Small Business Australia (COSBOA), and government officials from the Department of Industry, Science and Resources; Treasury; the Department of Education; and the Department of Health.

- Consultations internationally including with research sector representatives from the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (US).

Urgent need for policy reform

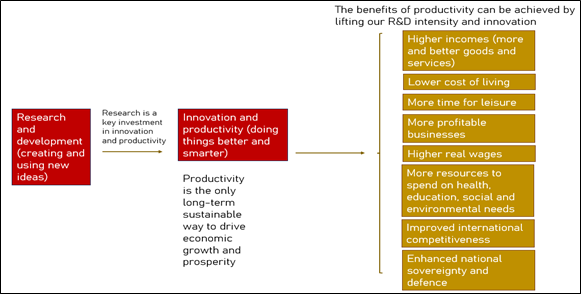

R&D is a critical enabler of innovation and productivity, and productivity is the long-term source of national prosperity, including higher incomes (business profits, real wages), lower cost of living, and more resources to devote to broader social, environmental and sovereignty goals (Chart 1).

R&D has a large payoff for Australia and that it is why it is critical for R&D intensity to lift. Empirical evidence from the CSIRO shows that Australian R&D supports high societal returns –an average economy-wide return of $3.50 for $1 of R&D investment.

Both business and higher education sector R&D needs to thrive

Revitalising R&D in Australia is not about prioritising one sector over another. Together the business and higher education sectors account for close to 90 per cent of R&D investment in Australia, and both need policy settings from government conducive to facilitating further R&D investment.

Higher education sector R&D is not ‘set and forget’

For the Australian higher education sector, the success of the Go8 in R&D should not lead to complacency nor lull policy decision makers into a ‘set and forget’ mentality. There are structural deficiencies in both current policy settings and funding of higher education R&D, including overreliance on cross subsidies required to cover the full economic costs of research, as well as reliance on international student revenue.

So, while currently the higher education sector R&D investment looks healthy, there are structural factors that point to risks that growth in higher education R&D will not be maintained. For example, the Australian Government is currently reviewing the National Competitive Grants Program (NCGP) structure but not the funding. The NCGP is only sustainable because of the significant co-contribution of universities which is contingent on cross-subsidisation of General University Funds to support both indirect and direct costs of NCGP research.

Lifting business sector R&D is critical

For the Australian business sector, in nominal dollar terms, more is invested in R&D today than ever before, but both in real terms and in terms of the share of the economy, business R&D investment has weakened since the global financial crisis (GFC).

As the SERD discussion paper recognises, business sector R&D as a percentage of GDP has declined from 1.37 per cent in 2009 to 0.88 per cent in 2022. R&D expenditure is a long-term investment and for Australia to lift its overall R&D performance requires an improvement in the conditions and incentives for businesses to invest.

Conclusion

Failure to achieve optimal investment in R&D today will mean the negative impacts on Australia’s innovation capacity and productivity are experienced many years into the future. Our recommendations to lift R&D intensity are intended to complement broader policy settings conducive to investment and economic growth.

We recognise that an R&D intensity target is not an objective in and of itself, but R&D intensity is a strong indicator of an economy’s long-term innovation and productivity potential.

By implementing our roadmap of reforms to raise Australia’s national R&D intensity, the Australian Government can drive Australia’s productivity potential that underpins our future prosperity. Now is the time for action.

Immediate term policy reforms that should be implemented within 1–2 years

Issue: Waning national R&D investment and direction

Go8 Recommendation: The Australian Government should formally adopt and implement a national R&D investment target of reaching 3 per cent of GDP by 2035 and adopt a 10-year horizon roadmap of reforms as proposed by the Go8.

Why we need a national target

Uplifting Australia’s overall R&D intensity is a national imperative, not just an aspirational ‘nice to have’. We have a long-term structural deficiency in productivity growth and R&D is one critical input to determining our innovation and productivity performance.

As the SERD discussion paper highlights, Australia’s R&D intensity has fallen from 2.24 per cent in 2009, to 1.66 per cent in 2022. Over this time other advanced and emerging economies have invested heavily in their R&D, knowing full well the importance of R&D for their future innovation, productivity and competitiveness.

Australia is significantly falling behind on this critical investment, resulting in Australia’s overall R&D intensity falling a full percentage point behind the OECD average. For the business sector which contributes 50 per cent of R&D investment, Australia’s lagging performance has resulted in an R&D intensity gap with the OECD average of over 1 percentage point.

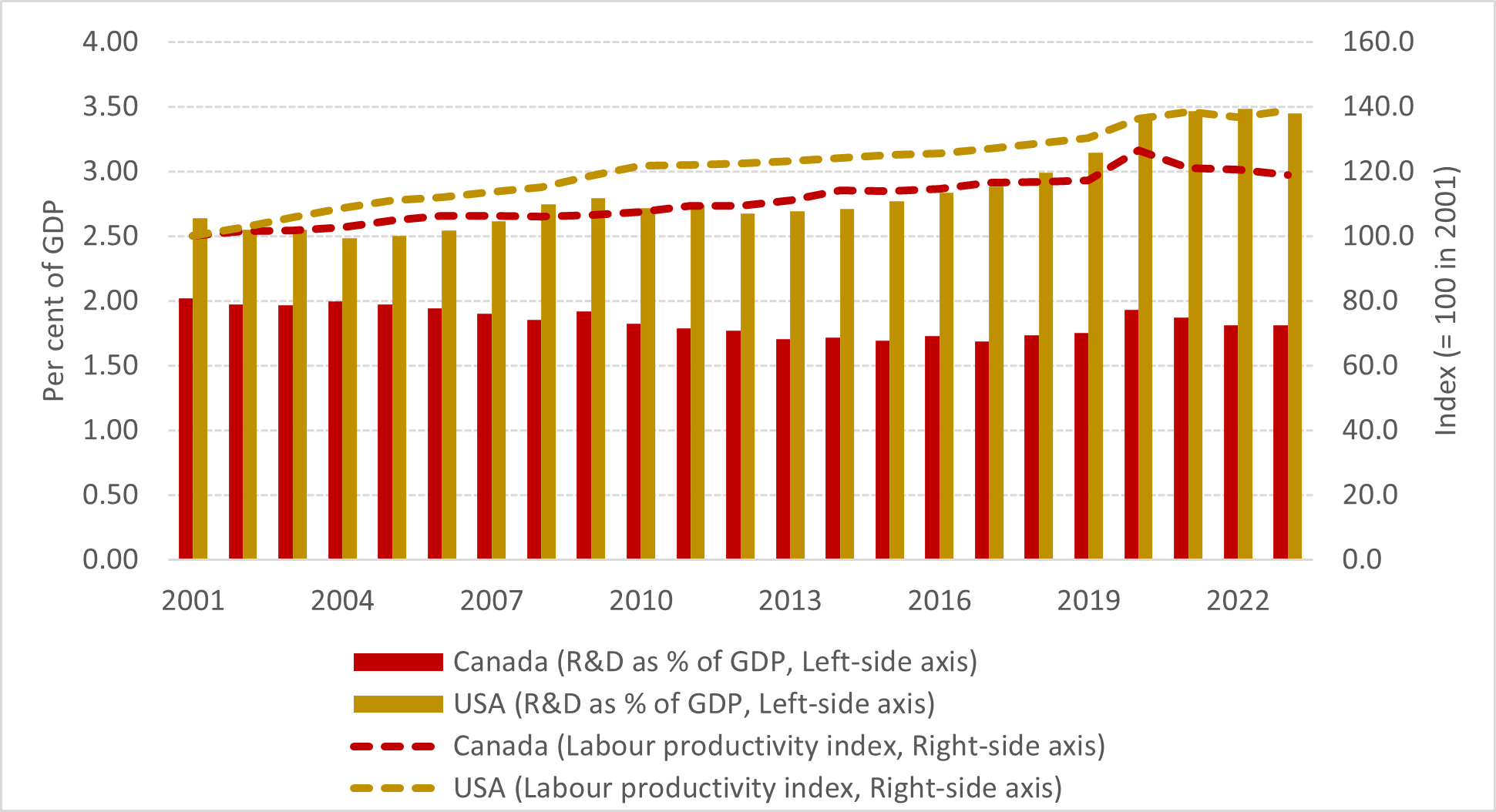

The experiences of two neighbouring modern economies, the United States and Canada, with similar access to knowledge, technology, and skilled labour, illustrate the potential role of cumulative investment in R&D (Chart 2).

Chart 2 shows that from the turn of the century the US has invested relatively more heavily in R&D as a percentage of GDP than Canada. At the same time their labour productivity performance has diverged, with the US improving more strongly than Canada. The stronger emphasis on R&D intensity in the US is one potential factor for this divergence.

Is there any evidence for choosing 3% of GDP as a national R&D target?

A national R&D investment target of 3 per cent of GDP has an evidence base behind it – first, economic modelling estimates for Australia provided in Chapter 3 of the Go8 report to the Australian Government: Australia’s research and development (R&D) intensity: a decadal roadmap to 3% of GDP indicate a societal optimal R&D intensity above 3 per cent of GDP, providing sound economic justification for such investment in Australia’s long-term innovation capacity. And second, Australian investment in R&D has a high societal return, estimated conservatively to be $3.50 on average for each $1 invested in R&D. The current Australian Government has a policy platform of “aspiring” to lift R&D to 3 per cent of GDP, but no coherent plan or timeline to do so. This is not going to address the gravity of our falling R&D intensity. It is time to move from aspirations to actions by committing to a clear national target. The target does not lock in government expenditure, it is about all sectors working towards a common beneficial national goal – prosperity by ensuring we remain a modern 21st century knowledge-based economy.

Issue: Fragmented approach to national R&D policy and measurement of progress

Go8 Recommendation: The Australian Government should establish a single overarching government agency for a whole of government approach to managing policy and funding for research and innovation. This new agency would develop and have the carriage to implement a national research strategy (informed by the outcomes of the SERD) towards a national R&D target.

A National Agency for Research & Innovation

The SERD Discussion Paper highlights Australia has a “patchwork” of funding and that R&D infrastructure lacks a long-term coordinated and national approach. The same can be said about overall R&D policy and programs in Australia, as well as the way in which Government itself procures research for its own use.

At the Commonwealth level we have a fragmentation and myriad of policies, programs, and agencies related to R&D across portfolios such as Industry/Science and Education, while taxation related initiatives, such as the Research and Development Tax Incentive (R&DTI), have been within the Treasury. Added to this we have multiple State and Territory programs and agencies.

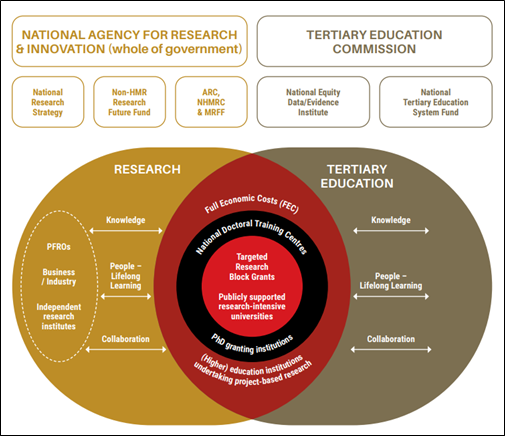

To improve R&D performance, there must be a national coordinated approach. At the Commonwealth level the Go8 proposes the establishment of a single National Agency for Research & Innovation to enable a whole of government approach to managing policy and funding for research and innovation. This new agency would develop and have the carriage of implementing a National Research Strategy towards a national R&D target.

Chart 3 illustrates the new agency within the broader architecture of a National Tertiary Education and Research System as discussed in the Go8 submission to the Australian Universities Accord in 2023.

A key task for the new agency would be to rationalise and coordinate government funding programs for research and innovation. According to the 2021-22 Science, Research and Innovation budget tables published by the Department of Industry, Science and Resources, the Commonwealth government invested $11.8 billion in research over 2021-22 through 157 distinct programs across 12 portfolios, including Education, Industry and Health. The procurement process for this research is ad hoc and varies between portfolios, with differing levels of support for indirect research costs.

Australia is too small to have such a fragmented research funding system. We need increased collaboration and more integration between the different funding bodies to provide greater economies of scale for our research efforts, reduce the bureaucratic burden on researchers and their institutions, and encourage greater collaboration between the different components of the research system.

Measurement of progress on national R&D investment

As a nation we need to more regularly measure overall progress on national R&D investment. R&D (expenditure) investment is measured by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) surveys for the four sectors: business; higher education; government; and private not for profits. However in recent years we have not had all the four sectors surveyed for the same year, so that total R&D investment (Gross Expenditure on R&D) is interpolated from the various inconsistent year sectoral surveys.

The Australian Government should support the ABS in annually surveying and reporting R&D (expenditure) investment for every sector of the economy, so we can better measure national progress. The Australian Government’s Measuring What Matters Framework should include the new target. To garner better measurement of the value and impact of R&D investments, the Australian Government should report annually on progress to achieve the target and also invest in improved measurement of the outcomes of publicly funded R&D.

Issues: The need for a consistent Australian Government research procurement policy and addressing the full economic cost of government research grants

Go8 Recommendations: The Australian Government should:

- Implement a consistent procurement policy where the Australian Government provides, as a transitional measure, at least 50 cents in the dollar of indirect cost support for all research procured; and

- Develop and implement a policy to provide the full economic cost of government research grants within a decade.

The higher education sector performs critical research for governments (Australian and State & Territories) as well as the business sector. The way in which this research is procured varies across portfolios.

The higher education sector contributes to the co-funding of its research and so has financial “skin in the game”. Universities such as the Go8 do this through, for example, utilising General University Funds as well as cross-subsidising research from international student revenue.

Even with contributions from university sources, funding from the government and business for this research frequently does not cover the full economic costs, resulting in research being conducted at a financial loss. The extent of this loss varies even for research done on behalf of Government portfolios as there is not a harmonised whole-of-Government procurement approach. This lack of consistency creates market confusion such that others who procure research, such as industry, have no consistent market signal as to likely indirect costs. Universities themselves are left to pay for the indirect costs of research done in the national interest, limiting what can be done to the extent of loss that can be absorbed.

The existing strategy does not guarantee the long-term sustainability of higher education research, nor does it allow universities to better serve the national interest.

What do we mean by full economic costs?

Full economic costs (FEC) include costs associated with “overheads” or indirect costs such as energy costs and building maintenance. Increasingly, universities are being asked to cover the indirect costs in addition to co-contributions to the direct costs of research. This is unsustainable and will limit the ability of universities to further contribute to national R&D at a time when business and government sector R&D investment intensity has waned.

Universities are research providers not research funders, and Australia’s national public research effort is subject to the variabilities of the international student market – a vulnerability that the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated is simply not sustainable.

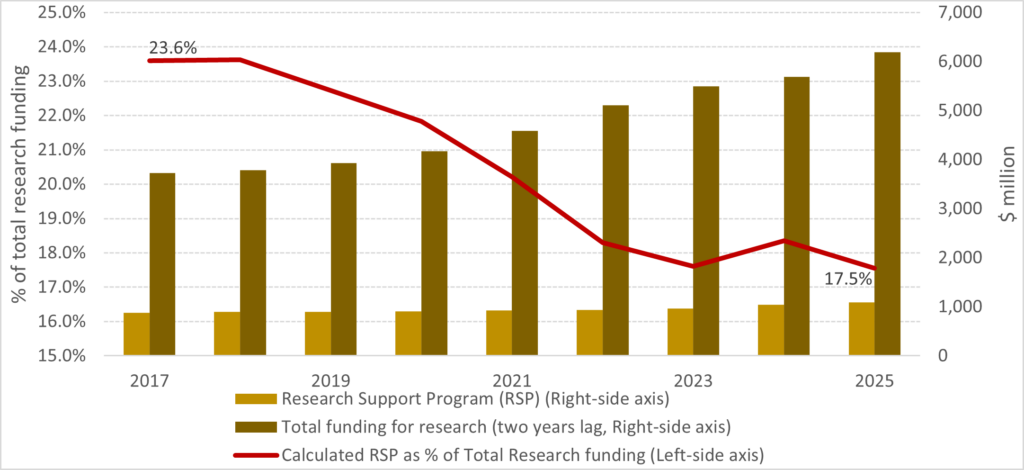

Illustration of declining support for indirect costs

Analysis shows that in 2025 the Research Support Program (RSP) was approximately 17.5 per cent of total research income reported (noting the two-year time-lag between the reported level of research income used to calculate the RSP distribution) whereas in 2017 this figure was 23.6 per cent (Chart 4). Since 2001 this support has more than halved (when it was 38.1 per cent) and compares to a Go8 estimate of $1.19 required to support indirect costs of every $1 of direct research income.

In the interests of universities further contributing to the national R&D effort, the Australian Government must address the full economic costs of research.

Issue: Improving industry-university linkages through national doctoral training centres

Go8 Recommendation: The Australian Government should establish national doctoral training centres that align with all key sectors of Australian economy and society and in areas of national priority.

The Australian Government should establish national doctoral training centres that align with all key sectors of Australian economy and society and in areas of national priority. These centres could leverage existing expertise within various universities and form across the private and public sector to provide critical mass and the necessary infrastructure for a high-quality student experience. Existing schemes such as National Industry PhD program could be aligned with these centres and industry invited to partner with them in a range of ways.

A well-trained research workforce is critical to Australia’s technological, cultural, and economic strength and its contribution to knowledge and prosperity locally and internationally. The nation needs creative and sustainable pathways to harness the intellectual talent needed to transform Australia. Graduate training is a key mechanism to build a knowledge economy. Although many PhD graduates remain in universities immediately after the completion of their degrees, only a small fraction remain in the university research system long-term. This is what some have dubbed the ‘Leaky Pipeline’ in academia, a rather deficiency-based viewpoint, predicated on the view that PhDs are only suitable for academic employment. But this is short-sighted. Rather, the purpose of research training is much broader and has much greater potential for a broader role in the private and public sector. A highly trained research workforce will increasingly become a vital aspect of Australia’s future economy and of benefit across a wide array of domains (i.e., business, government, public business enterprises, not-for-profit organisations, NGOs, community organisations).[2],[3]

Issue: Strengthening linkages between industry, universities and government and promoting translation of research

Go8 Recommendation: The Australian Government should build on the current Business Research and Innovation Initiative (BRII) within the Industry, Science and Resources portfolio, by introducing a Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) type program to incentivise SMEs to engage with Australian research institutions on R&D collaboration.

R&D activity involves knowledge creation as well as its application.

To support these elements by businesses in Australia, an immediate reform includes expanding the existing Business Research and Innovation Initiative (BRII) program within the portfolio of Industry, Science and Resources, which currently has budget funding until 2026-27, to include a United States style STTR type program targeting SMEs. This will facilitate increased R&D activity by SMEs in Australia and strengthen collaboration between businesses and research institutions.

What is a STTR program?

The BRII was modelled upon the US Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program. SBIR supports business to develop innovative solutions to public policy and service delivery challenges through supporting government procurement of products and services. In the US, the SBIR program was expanded to a complementary STTR program to access the research capability of research institutions to assist companies to develop early-stage technology readiness level (TRL) opportunities and provide SMEs surety of access to the underpinning IP within the research institutions. Evidence from the US on the value and impact of both the SBIR and STTR programs has been positive.[4]

The Go8, together with UniQuest at the University of Queensland, has developed a proposal for an STTR program in Australia. This program is designed to complement existing government initiatives. Our consultations have indicated broad support for the STTR proposal from the business community engaged in Go8 discussions.

A tangible way to strengthen industry-university-government linkages

The benefits of a dedicated STTR program to raise R&D intensity for businesses include:

- Providing a “whole of government” approach to R&D and innovation by SMEs.

- Assisting “technology pull through” by smaller businesses and their growth, including provision for SMEs to subcontract R&D to other businesses.

- Supporting government procurement of products and services.

- Diversifying from the reliance on the R&DTI as a driver of business investment in research and engaging SMEs across all priority areas of the National Reconstruction Fund at scale.

- Complementing the Australian Economic Accelerator, Trailblazer Universities Program, Industry Growth Program and National Reconstruction Fund.

A STTR program would encourage more R&D investment by SMEs and result in worthwhile smaller scale R&D projects with universities and other research partners that otherwise would not proceed. A STTR program therefore is a complement to incentivising more research at larger scale from our other recommendations, such as through establishing a fund similar in scale to the MRFF focused on fields of research outside of the MRFF.

While a STTR program for Australia would complement existing programs, it would also fill a gap within the suite of existing programs. This is because the STTR program would uniquely involve a combination of: formal R&D partnerships between small businesses and research institutions in areas broader than the mandates of existing programs; direct links to Australian government agencies extramural R&D budgets; and focus on R&D activity much earlier in the technology readiness cycle.

Issue: Intellectual property framework to encourage industry-university R&D collaboration

Go8 Recommendation: Clear and equitable strategies need to be developed by the Australian Government in partnership with universities and industry to promote and incentivise appropriate transfer and use of university IP, particularly in key identified areas of sovereign need or national strength, where the retention or majority control of that IP in-country supports national economic, social and other goals. These must however be matched by the investment to test (including via proof of concept) and commercialise such IP, as well as support for local capacity to develop, produce and manufacture the resulting technology or solution, and continued openness to trade ideas with like-minded partners.

Go8 Recommendation: The Australian Government reject any proposed overhaul of research-industry IP arrangements aimed at removing university institutions’ and creators’ rights to own the IP and shifting these rights wholescale to industry, or at diminishing the controls that the university creators have through a reduction of licensing arrangements.

The Go8 acknowledges that an increase in research commercialisation outcomes in Australia relies on effective, but appropriate, intellectual property arrangements that foster sensible, fair and collaborative sharing of IP with industry and other stakeholders.

There is no lack of willingness by Go8 universities to share their IP. Each of our members has expertise in negotiating and establishing meaningful collaborations with industry, whether for research contracting, research commercialisation or other research-based engagement.

As Australia strives towards sovereign capability in areas of key need and seeks to reap benefits in areas of national strength, improved conditions for home-grown IP to be effectively used are needed. It is not sufficient to enable the transfer and use of our university IP to Australian industry. Industry absorptive capacity as well as Australian capability to manufacture or produce resulting solutions, technology, plant varieties or other innovations – at scale – are also needed. The loss would not only be to Australia, but to the world, if the effective harnessing of our best IP stopped short and did not proceed, simply due to lack of Australian business take-up.

A refined approach is needed. The premise that IP from publicly funded research should not be owned by research organisations and researchers that created that IP – as has been advanced by certain parties – is flawed.

- As the two key Government funders of university research (the ARC and the NHMRC) have acknowledged, the ownership and the associated rights of all IP generated because of Australian Government competitively funded research are initially vested in the research institutions receiving and administering the grants as a way of recognising the inventive contribution made by the research institutions[5].

- Universities serve a public good, arguably mandated to do so to a greater extent than industry, and certainly more so than any individual company. Transferring ownership of ‘public good’ IP – for instance IP around treatment for an emerging pandemic threat – to a single company or set of companies risks resulting in reduced public good, both for Australia and the global community.

- From a practical perspective, it may be anti-competitive to transfer ownership of IP to single or even multiple industry recipients solely for their ownership and use, strangling any future opportunities for the use and even development of that IP.

- ‘Publicly funded IP’ is almost never solely funded by public funds. Universities invest significantly as co-funders of the direct and indirect costs of research. Often collaborators in the research include industry partners, government and publicly funded institutions, other universities and international parties, so an assumption that the IP is entirely government funded as the basis for making it freely accessible to all is flawed.

- Even the transfer of IP to Government in times of dire need occurs with protections for the owner of the IP. There is no blanket change of ownership to the Government in these emergency situations, rather a negotiation for use by Government[6].

More time is needed to understand if the Higher Education Research Commercialisation Intellectual Property (HERC IP) arrangements recently introduced by the Australian Government to promote easier and readier IP sharing arrangements between universities and industry have had a positive effect as intended.

Go8 Recommendation: The Australian Government should boost the effectiveness of the Higher Education Research Commercialisation Intellectual Property Framework by revising the template agreements provisions to address inappropriate liability provisions and unreasonable intellectual property indemnities for universities as public institutions. Maintain these agreements as voluntary to use.

The Australian Government should improve the Higher Education Research Commercialisation Intellectual Property Framework by revising the template agreements to address liability provisions and intellectual property indemnities. These templates, which should stay voluntary, need adjustments to be more appealing for use. The goal is to boost R&D and collaboration between businesses and universities.

Issue: Maximising the value of existing investment in R&D and driving greater R&D investment by industry

Go8 Recommendation: The Australian Government should leverage the Research and Development Tax Incentive (R&DTI) by offering an additional equity or debt finance incentive from the National Reconstruction Fund (NRF) to businesses that qualify for the R&DTI and enter into formal R&D collaboration with an Australian research institution.

Recognising the R&DTI regime is well regarded as being an effective facilitator of additional R&D investment and has established parameters, its effectiveness would be further boosted by offering businesses that qualify for the R&DTI and who enter formal R&D collaborations with an Australian research institution, an additional equity or debt finance incentive from the National Reconstruction Fund (NRF).

This reform focusses on business R&D at the applied/development end of the R&D spectrum, and hence more likely to be within the NRF mandate to achieve a target portfolio rate of return of 2–3 per cent above the 5-year Australian Government Bond rate over the medium to long term. Assessment of the R&D activity can continue to be done through the administration of the R&DTI program by the Department of Industry, Science and Resources/ATO and formal collaboration with an Australian research institution can also be assessed through this administration.

Issue: Boosting skilled migration

Go8 Recommendation: The Australian Government should boost Australia’s R&D workforce through skilled migration:

- Under the new Skills in Demand visa as part of the Migration Strategy, provide direct and expedited permanent residency for international students obtaining a PhD at an Australian university, in areas of identified critical need.

- Through the new National Innovation visa, develop a national strategy to actively attract and retain high-quality international researchers.

To achieve the proposed lifting of Australia’s R&D intensity requires a suitably skilled research and development workforce. Having a national target to significantly lift R&D intensity without commensurate growth of the research workforce will result in the target not being met. So, supply side measures to increase the R&D workforce are needed as part of the national strategy.

The research workforce needs to be expanded from both domestic and international sources. In terms of international sources for expanding Australia’s research workforce, the Australian Government’s announcements of a new Skills in Demand visa, under its recent Migration Strategy, provides a promising avenue. The objective of augmenting Australia’s research workforce can be pursued by the Australian Government using the new Skills in Demand visa to provide direct and expedited permanent residency for international students obtaining a PhD at an Australian university in areas of identified critical need.

In 2022 there were approximately 4,000 international students graduating with a PhD from a higher education institution in Australia (approximately 50 per cent of these are from Go8 universities). Not all international students graduating with a PhD will want to become permanent residents of Australia, but those that do will significantly contribute to the scale and capability of the domestic research workforce, especially in critical areas such as STEM. The Australian Government has also announced a new National Innovation visa to target exceptionally talented migrants for sectors of national importance. Through the new National Innovation visa, the Australian Government should develop a national strategy to actively attract and retain high-quality international researchers. These initiatives should complement the expansion of Australia’s research workforce from domestic sources, as discussed in the next recommendation.

Issue: Investing in Australia’s domestic research workforce

Go8 Recommendation: The Australian Government should further invest in the domestic R&D workforce by:

- Prioritising reforming university funding rates and levels for STEM related fields of education to raise STEM supply through universities.

- Ensuring stipends and scholarships for higher degree by research students are attractive to retain and grow the pool of researchers in Australia.

Boosting Australia’s research workforce also requires that the Australian Government acts on the Australian Universities Accord Review Panel (2024) recommendation to increase government funding to support STEM courses to reduce the negative impacts of the existing Job-ready Graduates (JRG) package. The Accord Panel recommended that any early Australian Government investment in response to the Accord should prioritise the STEM disciplines.

Further immediate reforms related to the research workforce include ensuring stipends and scholarships for higher degree by research (HDR) students are attractive, to retain and grow the pool of researchers in Australia. The Australian Universities Accord Review Panel (2024) also makes this recommendation.

Issue: Elevating Indigenous peoples in our R&D system

Go8 Recommendation: The Australian Government should continue to develop measures to protect Indigenous knowledge by implementing Indigenous data sovereignty and protection of Indigenous cultural and intellectual property.

As noted in the SERD discussion paper, there is a need to ensure proper representation of Indigenous knowledge in the Australian research system. In addressing these issues, intellectual property arrangements should ensure Indigenous data sovereignty, as well as protection of Indigenous cultural skills and practices, as part of a broad-based protection of Indigenous cultural property.

Medium term policy reforms that should be implemented within 3 to 5 years

Issue: Pursuing global R&D partnerships

Go8 Recommendation: The Australian Government should pursue Australia’s participation in globally leading-edge research consortia and collaborations such as Horizon Europe.

It is critical that the Australian Government begin pursuing association to Horizon Europe’s successor from 2028, the 10th EU Framework Programme for Research and Innovation (FP10), whose recommended budget is in the EUR 200 billion range[7]. This is important because it opens up new opportunities globally, and further integrates Australian businesses and researchers into R&D globally. We have seen recently that one source of international funding, the United States Government, has come under stress, so ideally Australia should diversify its international funding sources and collaboration networks. While Australia has in place the Global Science and Technology Diplomacy Fund, as a nation we should go further and pursue Australia’s participation in other globally leading-edge research consortia and collaborations such as Horizon Europe.

Issue: Access to (private) finance for R&D

Go8 Recommendation: The Australian Government facilitate the presence of additional intermediaries and aggregators (between superannuation funds as investors and early-stage enterprises as investees) to encourage expenditure on R&D.

The $3.5 trillion superannuation industry is a growing source of capital in Australia’s economy and within their mandates and duties to members, some superannuation funds such as Hostplus are already investing in early-stage seed investments. Recent media reports also point to Australian superannuation funds increasingly investing in UK early-stage ventures associated with UK university research.[8] The Australian Government is also providing support through its Early-Stage Venture Capital Limited Partnerships (ESVCLP).

The UK has previously announced reforms to its financial services sector as part of its “Mansion House Reforms” that include an agreement between nine of the UK’s largest defined contribution pension funds to commit to allocating 5 per cent of assets in their default funds to unlisted equities by 2030.[9] In the Australian context, to further build the contribution of superannuation funds in boosting investment in early-stage R&D ventures, including collaborations between SMEs and Australian universities, the Australian Government should facilitate the presence of additional intermediaries and aggregators (between superannuation funds as investors and the early-stage R&D-based ventures as investees). The role of these intermediaries would be to ultimately broker the relationship between the two so that promising early-stage R&D-based ventures are brought to the attention of Australian superannuation funds for consideration. The Australian Government could facilitate this through its existing programs related to early-stage investment, or a new dedicated program.

Issue: Sustainable national research infrastructure

Go8 Recommendation: The Australian Government should facilitate sustainable national research infrastructure by moving the National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy program to a future fund style of funding and, in collaboration with State Governments and Universities, undertake a comprehensive review of governance and administration of the program and existing funded facilities.

- Adopting a life-cycle approach to funding for national research infrastructure;

- Specifying a requirement to aim for productive engagement and partnerships between researchers, industry, State Governments, and the broader community; and

- Including explicit provision for researchers to access priority international research infrastructures.

It is critical that research linkages between business and the research sector also encapsulate collaboration on utilisation of research infrastructure. The final report of the Australian Universities Accord Review Panel (2024) recommends the Australian Government provide stable and predictable ongoing funding for the NCRIS. Building on this, in the three to five year period of our proposed roadmap, the Australian Government can maintain momentum towards a national R&D intensity target by securing and strengthening investment in the NCRIS program and making national research infrastructure a catalyst for further business-research collaboration.

This would involve:

- Moving the NCRIS program to a future fund style of funding and undertake a comprehensive review of governance and administration of the program and funded facilities.

- Adopting a life-cycle approach to funding for national research infrastructure, including capturing ongoing maintenance and operation costs of the infrastructure and the skilled workforce required to support world leading facilities. The emphasis would be on identifying opportunities to build scale, taking advantage of local research strengths and critical mass, including those in the private sector and broader community.

- Specifying a requirement that custodians and users of the national infrastructure, wherever possible, seek out, promote, and enable productive engagement and partnerships between researchers, industry and the broader community.

- Including explicit provision for researchers to access priority international research infrastructure.

Issue: A macroeconomic environment conducive for domestic R&D and innovation

Go8 Recommendation: The Australian Government should continue to pursue an open trading system, including reducing non-tariff barriers to trade in services. In addition, competition reforms should be pursued to rebuild the momentum of a dynamic economy achieved by competition policy reforms in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Trade openness contributes to innovation and knowledge diffusion. The Australian Government has acted to negotiate and agree free trade agreements and reduce Australia’s statutory import tariff levels towards zero. Despite the current volatile geopolitical environment and move towards tariff and other trade barriers internationally, the Australian Government should continue to pursue an open trading system. Achieving progress to a national R&D target can also be strengthened over the medium term by successfully implementing recently announced competition related reforms, rebuilding the momentum of a dynamic economy achieved by competition policy reforms in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Longer term policy reforms that should be implemented within 6 to 10 years

Issue: Mission-oriented policies

Go8 Recommendation: The Australian Government should establish a fund similar in scale to the Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) focussed on fields of research outside of the MRFF.

The early success and focus of the MRFF on translation of health and medical research is a template for other areas of research in Australia. A national R&D intensity target could therefore be further achieved by, over the longer term, establishing a future fund for other fields of research.

A fund for research in fields outside of the MRFF concentrations, with a strong link to basic research, is important because basic research can deliver the pipeline of ideas, technologies and processes that be built upon in the future. In Australia, business expenditure on basic research is only around 10 per cent of total business R&D expenditure.

Issue: Innovation hubs supporting knowledge sharing and transfer

Go8 Recommendation: The Australian Government should work with States/Territories and local government to coordinate existing programs and support to incentivise development of knowledge precincts through co-location of Australian universities and businesses.

All levels of government should collaborate to incentivise co-location of science-based universities and businesses. Evidence suggests the development of ‘knowledge precincts’ creates positive innovation and productivity spillovers to businesses.[10] For example, Monash University and Moderna, with government support, have established a 5-year partnership program which aims to drive advancements in mRNA medicines, including therapeutics and vaccines. There are countless other examples and new opportunities for industry to explore with university partners and facilitated by government.

The Australian Government should work with States/Territories and local government to coordinate existing programs and support to incentivise development of knowledge precincts through co-location of Australian universities and businesses.

Issue: Open access to research to promote its dissemination and adoption

Go8 Recommendation: Implement open access to research principally funded by the Australian Government in a way that does not result in extraction of rents by publishers from researchers and readers but acts to increase knowledge available to businesses and improve diffusion of knowledge.

R&D most effectively translates to innovation and productivity if R&D activity involves knowledge creation as well as its adoption and adaption. Adoption and adaption of R&D by businesses, particularly SMEs that have more limited financial resources, can be stifled by research which is non-rival but excludable. That is, excludable by access to research being limited to only paying customers.

The Australian Government should implement open access reforms to research principally funded by the Australian Government, in a way that does not result in extraction of rents by publishers from researchers and readers but acts to increase knowledge available to businesses and improve diffusion of knowledge.

Open access to this type of research is raised as a reform by the Productivity Commission (2023), but as Holden (2021) notes , the way open access is implemented is important so as to avoid rent extraction.[11][12] For example, Holden points out that publishers requiring researchers to pay for open access to their published works can result in large fees being paid to publishers that could otherwise be used to fund additional research.

Issue: Basic Research – fundamental to everything

Go8 Recommendation: Sustainable increased funding for basic research, both in the higher education sector to foster and consolidate university activity, and in industry sectors that rely on it.

No strategic examination of R&D can fail to recognise the vital relevance of basic research, whose impacts and influence occur pervasively across the R&D spectrum, in underpinning, driving and facilitating progress toward applied solutions and the pursuit of experimental development.

The reference in the discussion paper that ‘Australia is left with an unbalanced innovation ecosystem where basic research capacity is not matched to investment in translation’ is both facile and inaccurate. By its very nature, basic research will have impacts beyond single human lifetimes and cascading and ongoing relevance to future discoveries, applications and breakthroughs. As the Go8 has previously emphasised, the link between basic research in one field and its broader application is not often evident or immediate (Go8 2023, Basic Research: the foundation of progress, productivity, and a more sovereign nation).

The Go8 rejects the mischaracterisation of basic research as an element that is overinvested in by comparison to translation. Aggregate spending across sectors on basic research in Australia has declined since 2012 when it peaked at $8.2 billion (Go8 2023).

Instead, the Go8 calls for sustainable increased funding for basic research, both in the higher education sector to foster and consolidate university activity, and in industry sectors that rely on it, including sectors such as defence, quantum and AI.

[1] Australian Universities Accord Review Panel. (2024). Australian Universities Accord Final Report, Canberra.

[2] McGagh J, Marsh H, Western M, et al. Research training system review. 2016. https://acola.org/research-training-system-review-saf13/

[3] Vitae. Researcher training — Vitae Website. Vitae, Realis. potential Res. 2020.https://www.vitae.ac.uk/researcher-training

[4] For example, see Howell, S. (2017). ‘Financing innovation: evidence from R&D grants’, American Economic Review, 107(4), April, pp. 1136-64; and also: Bottai, C., de Rassenfosse, G., & Raiteri, E. (2025). ‘A new approach to measuring invention commercialization: an application to the SBIR program’, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5167124.

[5] ARC and NHMRC 2022, National Principles of Intellectual Property Management for Publicly Funded Researches (sic)

[6] https://www.ipaustralia.gov.au/understanding-ip/who-owns-ip

[7] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-10-2025-0028_EN.pdf

[8] van Leeuwen, H. (2024). ‘Why Hostplus is doing the UK differently’, The Australian Financial Review, 18 March. https://www.afr.com/markets/equity-markets/why-hostplus-is-doing-the-uk-differently-20240318-p5fd3r

[9] HM Treasury. (2023). ‘Chancellor’s Mansion House reforms to boost typical pension by over £1,000 a year’. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/chancellors-mansion-house-reforms-to-boost-typical-pension-by-over-1000-a-year

[10] Bloom, N., Van Reenen, J., & Williams, H. (2019). ‘A toolkit of policies to promote innovation’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(3), Summer, pp. 163–184.

[11] Productivity Commission. (2023). 5-year Productivity Inquiry: advancing prosperity. 5-year Productivity Inquiry Report, Canberra. https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/productivity/report

[12] Holden, R. (2021). ‘Open access, market power, and rents’, VerfBlog, 2021/12/21, https://verfassungsblog.de/open-access-market-power-and rents/,DOI: 10.17176/20211221–235850-0